10 Latin American authors chose these objects to write captivating stories

10 Latin American authors chose these objects to write captivating stories

Through the Untold Microcosms project, with SDCELAR and Hay Festival Inertnational, Latin American authors devised fiction and non-fiction stories inspired by the Museum’s Central and South American collections.

The authors worked closely with SDCELAR curators to explore their chosen pieces’ historical and political context. Pottery figurines, masks, spoons, and ornaments from diverse areas in the region are some of the items that caught the attention of these writers.

The book ‘Untold Microcosms: Latin American Writers in the British Museum’ has been published by Charco Press in English and can be ordered online. Here you can have a sneak peek of the authors’ objects and stories.

In The Land of The Weeping Trees, Joseph Zárate

Excerpt

‘Countless native people were tricked when it came to their wages, paid in cheap liquor that kept them in a state of stupefaction, were beaten if they didn’t comply, while others died of starvation, dysentery and other diseases, while their women and children were used as servants or to do unpaid work in the fields. Over all of this barbarity rose the splendour of Iquitos, known at that time as the ‘Wall Street of Rubber’.

It was in this world of bonanzas and atrocities, where the indigenous people were seen as savages, almost as animals, deprived of intelligence and qualities, that my great-great-grandfather Rafael Tuanama worked’.

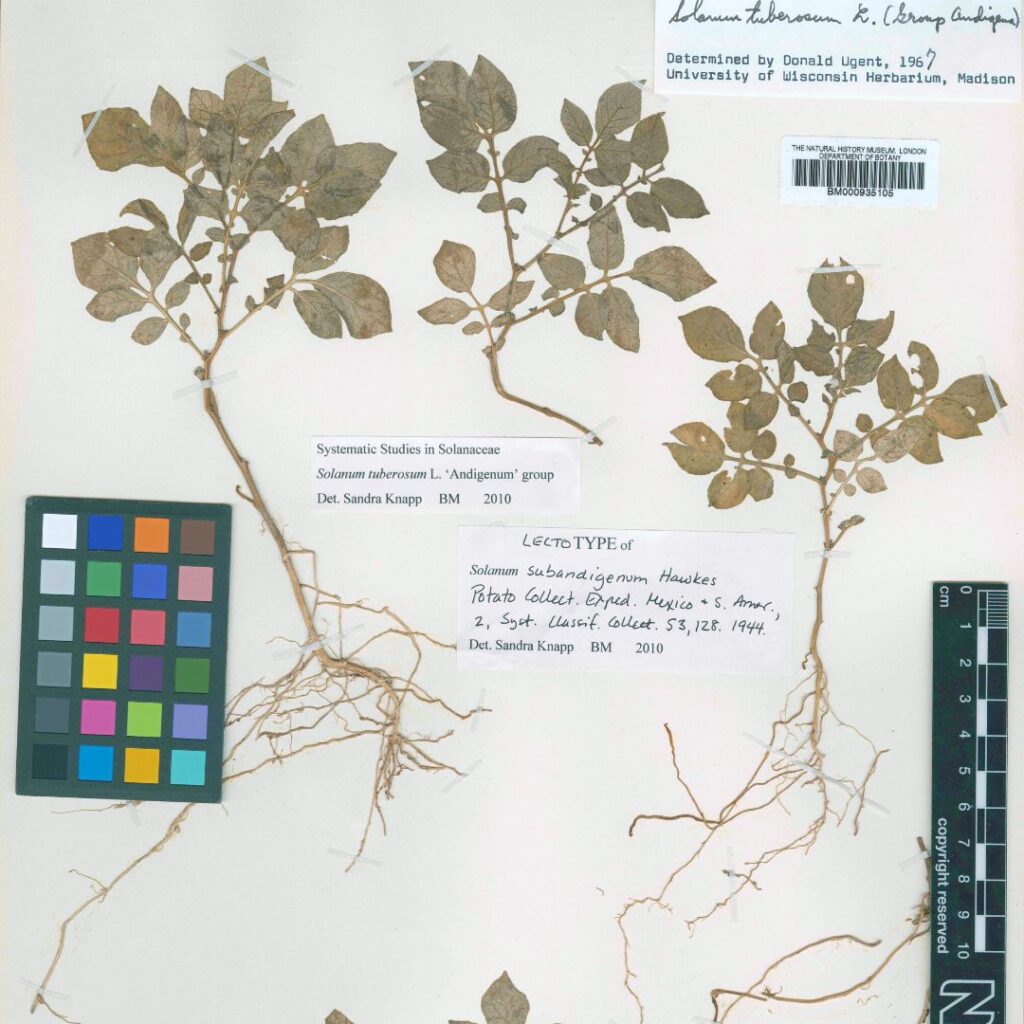

Late Blight, Cristina Rivera Garza

Excerpt

‘Of course no one lived here. Of course the cave was permanently uninhabited. Sealed off from humanity. Except for them. The plants. Except for these long vertical roots that travelled towards the centre of the earth, loaded with tubers four to six centimetres wide, a thin layer of pale skin filled with eyes and this juicy flesh, packed with starch and vitamin C, slightly acidic to the taste. There was nobody here except for them and these walls of igneous rock, which loomed over the stony ground, frankly dour, with the weight of centuries’.

Heritage, Carlos Fonseca

Excerpt

‘Perhaps this is why, though almost three decades have passed since those childhood afternoons, as I listen to the curator recount the odyssey of the solitary Sororeng, who acted as interpreter for Schomburgk on his southern voyages, I find myself distractedly thinking about grandfather’s flowers. El viejo could never have imagined that I would one day find myself standing in front of cabinets filled with the wonders Schomburgk first donated to the British Museum on his return from Guyana in 1939. Before me on the shelves, the pieces from the collection trace the images that Isabel is describing‘.

Otilio, Velia Vidal

Excerpt

‘Perhaps to encourage me with my writing, my mum gave me a gold bracelet that she’d been left by my dad. The moment I saw it, I recognised the letters written on the metal and knew we had the same name. That was really exciting. She also told me a fuller version of her life story, which I’d heard bits of during her conversations with my godmother, as they sat drinking viche liquor and joking about what the black people said about the Wounaan and the Wounaan about the black people. They laughed at their luck: Justina hadn’t been able to have children and it was like a curse, she said, because her husband Antonio had used it as an excuse to make another home in Palestina. She pretended not to know’.

The Strenght of Exu, Djamila Ribeiro

Excerpt

‘Itãs are phrases from time immemorial that refer to the mythical tales of the Yoruba tradition. ‘Exu killed a bird yesterday with the stone he threw today’ is one of the best known. Which was why I had no doubts about choosing the object representing Exu to inspire this text, a part of the British Museum collection. Exu is the first of the orixás, the lord of the pathway who enjoys a good laugh. The Catholic Church did not wish to understand, so they syncretised him with the devil and persecuted whoever spoke his name. But Exu laughs at that definition, too. Exu is not goodness, nor evil, but contradiction, uneasiness, change’.

The Wichí Community, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara

Excerpt

‘What they do when they do what they want is of an extraordinary beauty. Objects that smell of the forest and glow in their woven splendour. Objects that you can appreciate with your nose, your skin and your eyes. Yicas, backpacks, purses, handbags. And huge shawls that explode with colours; they are abstract in their design even when they have some figurative details. Lysergic explosions full of life. Contrasts, frictions and tensions that make us quiver. Checkerboards, mermaids, diamonds, uninterrupted lines that go up and down like snakes trained to slither in straight lines. Gigantic maps of a foreign territory. These objects and works are excessive. They exceed all frames of reference, because they were not conceived for our world’.

Extract From The Diary Of A Journey Along The North Coast Of Peru – Juan Cárdenas

Excerpt

‘A small huddle of curious onlookers forms around him and, after much discussion, there is still no agreement about the appropriacy of the figure. Some consider it scandalous and demand it be destroyed before any member of the priestly caste can see it. Others, more daring in their outlook, proclaim a radical change in the canons of the representation of the gods and their prowess. The young artist attempts to defend his piece with pious arguments in keeping with the doctrine, but his words fall on deaf ears because the figure has already provoked such controversy’

The Names of The Trees, Dolores Reyes

Excerpt

‘ << We’re going to return their names to the ground so that tomorrow, the rays of sunlight will transform them back into trees. And if we can’t find the goddess of the ground, we’ll make our own goddess out of the ground using our bare hands >>, says Big Grandma, looking at me as a reminder that it’s my job to whisper all the names to the goddess so she can bring them back.

But we’ve been searching for ages in the darkness and we haven’t found her. We need to reach ground that is not sick from fear nor fire. The seven of us trudge slowly along through the blackness, our bodies bumping into each other.

Will this night never end?’

Tongues Hanging Out, Lina Meruane

Excerpt

‘The horror of exploitation never ended, but merely changed shape. Now it was self-exploitation, but it wasn’t voluntary, not exactly. Because behind it was job insecurity and economic inequality and the need to survive without help of any kind – that was the economic strategy employed by some to force others into ceaseless work. Consumed by the competitive logic of every man for himself, we had not only acquiesced, but also agreed to add hours to our work days. As if we were flaunting a power, as if we possessed a superior virtue’.

Publications related to women’s and maternal health with Wixárika communities by the author of this exhibition

Gamlin, Jennie B. (2013)

Shame as a barrier to health seeking among indigenous Huichol migrant labourers: An interpretive approach of the “violence continuum” and “authoritative knowledge”

Social Science and Medicine 97 75-81

Gamlin, Jennie B. (2023)

Wixárika Practices of Medical Syncretism: An Ontological Proposal for Health in the Anthropocene

Medical Anthropology Theory 10 (2) 1-26

Gamlin, Jennie B. (2020)

“You see, we women, we can’t talk, we can’t have an opinion…”. The coloniality of gender and childbirth practices in Indigenous Wixárika families

Social Science and Medicine 252, 112912

Jennie Gamlin and David Osrin (2020)

Preventable infant deaths, lone births and lack of registration in Mexican indigenous communities: health care services and the afterlife of colonialism

Ethnicity and Health 25 (7)

Jennie Gamlin and Seth Holmes (2018)

Preventable perinatal deaths in indigenous Wixárika communities: an ethnographic study of pregnancy, childbirth and structural violence BMC

Pregnancy and Childbirth 18 (Article number 243) 2018

Gamlin, Jennie B. and Sarah J Hawkes (2015)

Pregnancy and birth in an Indigenous Huichol community: from structural violence to structural policy responses

Culture, health and sexuality 17 (1)