Blackwell School: A History of Latinx Segregation in Texas

Education for local children of Mexican descent in Marfa, Texas, dates from 1885 when the first school opened in Marfa for all children. A new elementary school was built for the Anglo children in 1892 and students were separated by ethnicity. In 1909 the School Board authorized money for a new schoolhouse for Latinx children (by then called ‘Hispanic’): the building we commemorate today as the Blackwell School.

Schoolhouse c. 1930

Unlike African Americans, Latinx people in Texas were not subject to segregation by state laws. Instead, Texas school districts regularly established schools for Mexican Americans through de facto segregation. The Blackwell School is a tangible reminder of a time when the practice of “separate but equal” dominated education and social systems. Despite being categorized as “white” by Texas law, Mexican Americans were regularly excluded from commingling with Anglos at barbershops, restaurants, funeral homes, theaters, churches, and schools.

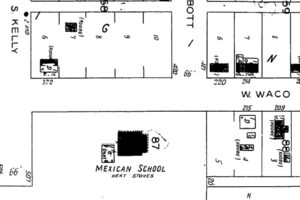

Sanborn Map, 1933

Known originally as the Ward or Mexican School, the school was named in 1940 for longtime principal Jesse Blackwell. As the student population grew to the hundreds, more buildings were constructed next to the 1909 schoolhouse and a bustling campus anchored the ‘Hispanic’ neighborhood of Marfa.

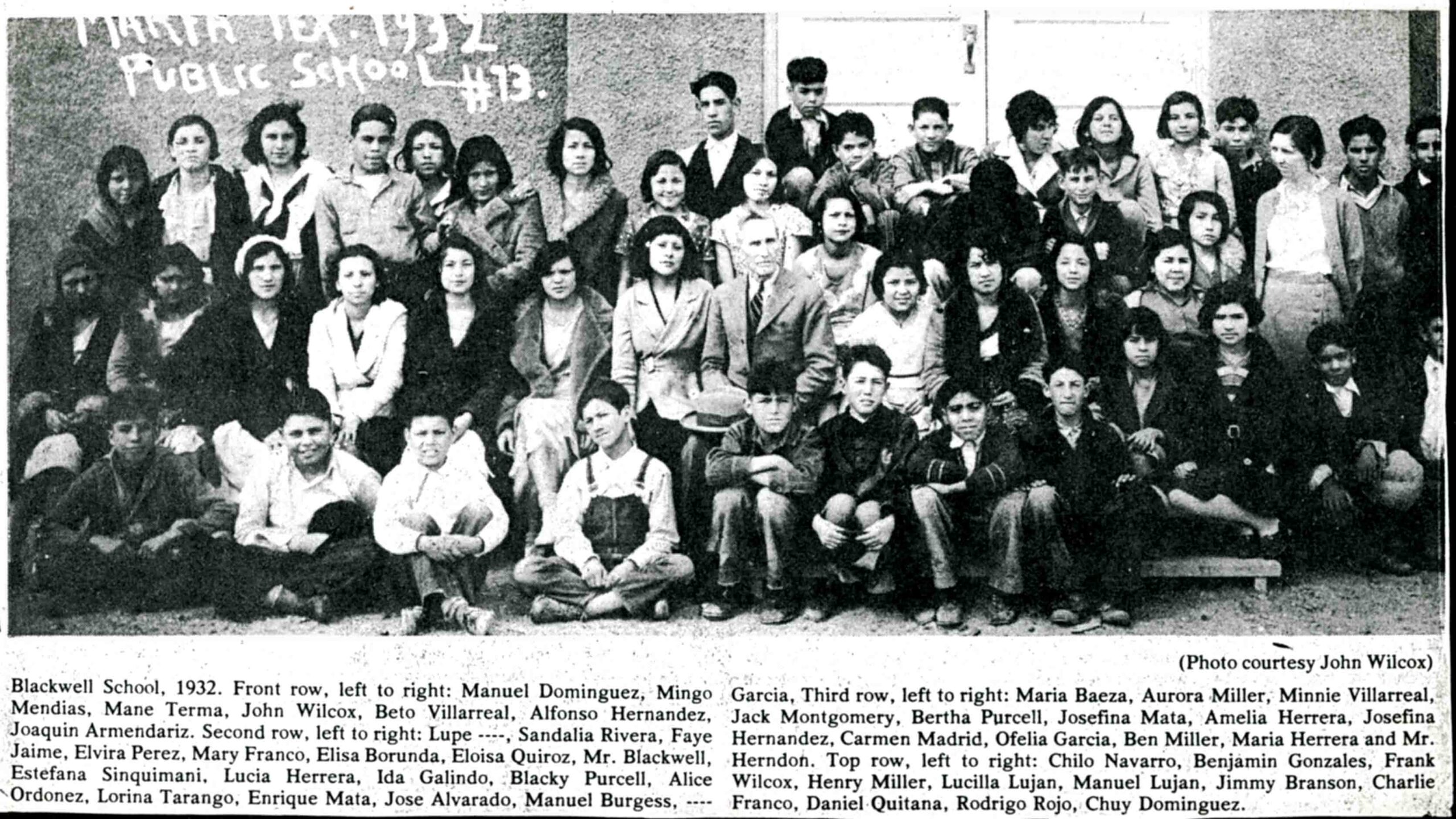

Students, 1932. Jesse Blackwell at the centre

Mexican and Mexican American culture in Marfa, Texas, is tied to the Blackwell School through the more than fifty years that Blackwell School served as a school and the leading feature of the Latinx community of Marfa, illustrating the challenge of maintaining cultural identity in a dominant Anglo society.

The spectrum of experiences of students and teachers at the ‘Hispanic Blackwell School’ constitute an important record of life in a segregated institution in the context of the history of Texas and America. Students were taught only in English from the beginning, yet in 1954 the school implemented a strict policy of no Spanish spoken anywhere on campus. Administrators created a mock funeral ceremony where students wrote on slips of paper and buried the Spanish language.

Blackwell playground c. early 1950s

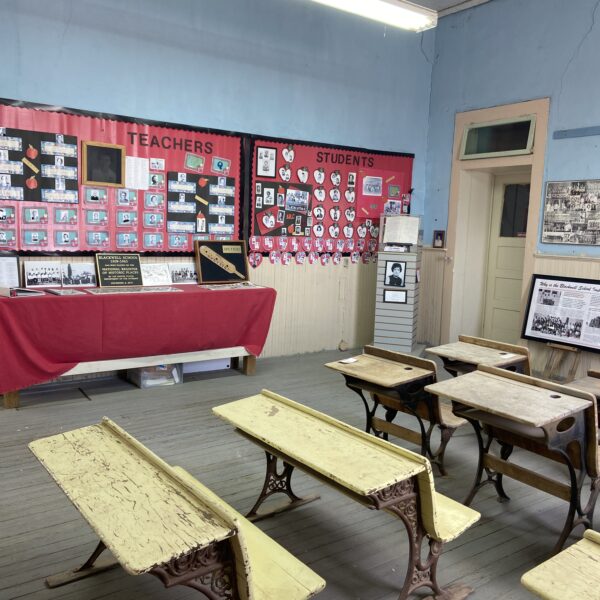

Marfa schools integrated in 1965, and most of the buildings of the Blackwell School were torn down within a few years. The original adobe, however, was kept and used by the school district for many years as a vocational school for high school students. Finally, the building was relegated to storage. In 2006, a group of former students learned that the last remaining building was threatened with disposal. They met with the Marfa School Board and asked for a reprieve. They explained that this building belonged to the students, the neighborhood, and the city of Marfa. They offered to dedicate themselves as the Blackwell School Alliance to preserving the historic building and its legacy.

Today, the Alliance has succeeded beyond its wildest dreams. On October 17, 2022, President Biden signed the law creating Blackwell School National Historic Site as part of the National Park Service. With the transfer of the property to the National Park Service, the Alliance has achieved its primary goals of preserving the building and creating a museum.

Blackwell School building, August 2022

This project will create four grade-specific standards-based lesson plans for use in Texas schools to teach about the Blackwell School and the history it represents. The Alliance will shift to a mission of education and outreach. Academic research, combined with oral histories and community conversations, form the foundation for educating visitors and stakeholders, including school children, about this neglected piece of our history. New curriculum products will bring students to the Blackwell School—in person and virtually—to learn and understand the experience of students and staff, placed in the context of Mexican American schools of that era and the broader experience of Mexican Americans in this country.

STAY UPDATED >> For more about this and other projects follow us on Facebook and Instagram.