All Projects Isthmo-Colombia Healing Words, Resistance through Indigenous Memory

The museum exhibition ‘Endulzar la Palabra, Memorias Indígenas para Pervivir,’ which has been loosely translated as ‘Healing Words, Resistance through Indigenous Memory’, presented in 2018 at the National Museum of Colombia, is a collaborative exhibition curated between the National Centre for Historical Memory and various Indigenous peoples from Colombia. It is based on their responses to the impacts of the armed conflict and the construction of their own historical memory.

This exhibition was led and organised by local researchers from the participating communities. It was designed on the premise that Indigenous groups have different ways of conceiving the past and their memories, which are closely linked to their survival.

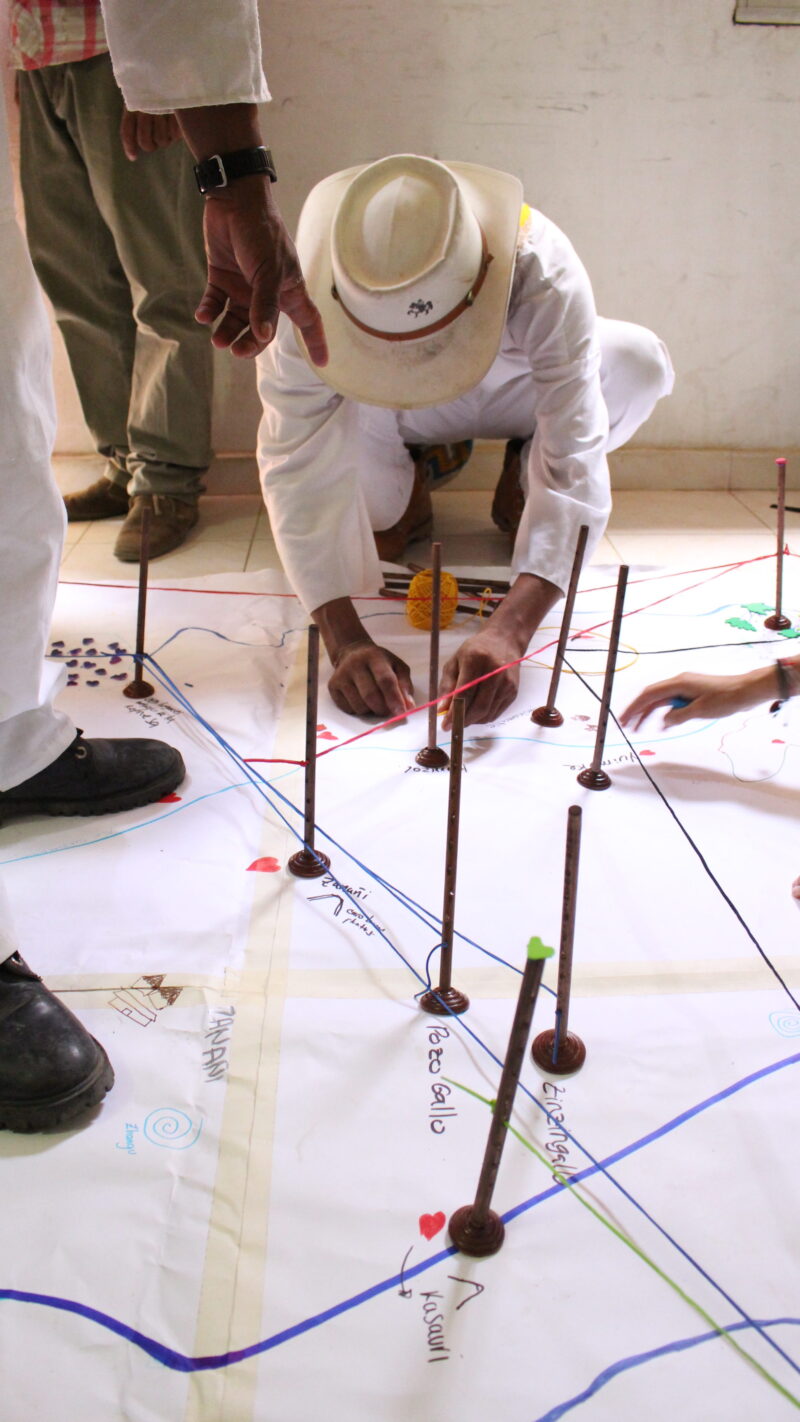

Members of the Wiwa community creating a string map to illustrate features of their sacred landscape, photo by Celia del Pilar Paez Canro

A member of the Wiwa community connecting the strings in order to illustrate how an event in a sacred site has impact in other sites, photo by Celia del Pilar Paez Canro.

A member of the Wiwa community locating sacred places within the landscape, photo by Celia del Pilar Paez Canro

In the case of the Wiwa community from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the first step in this post-conflict healing process was to re-appropriate the territory by traveling through it and marking it. Although more than 70 sacred Wiwa places in their territory have been affected by a foreign violent conflict, they still believe that it is possible to restore their spatial equilibrium. Each of these sacred places are associated with particular phases of the life cycle, and are interconnected with each other and with hundreds of other places scattered in the Sierra Nevada as well as with places as far away as the mountains that surround Bogotá.

Members of the Wiwa community creating a string map to illustrate features of their sacred landscape, photo by Celia del Pilar Paez Canro

To record and disentangle the web of relationships that constitute and ensure the balance in the territory was an enormous task since the Western maps created by local researchers only managed to record the location and attachment to the places, but failed to encapsulate the context of the relationships between them. As we would come to understand later, the sacred places are displayed in terms of nine dimensions represented with different colours. In this way, the local researchers, with the support of their traditional authorities, were given the task of constructing a map that allowed us to express the different dimensions of cultural damage that the war inflicted more clearly .

Only at that moment was it possible to understand that impact on just one of these places could affect the balance of the entire network of sacred places expressed in the cartography of the Wiwa people, which ultimately extends throughout the entire territory.

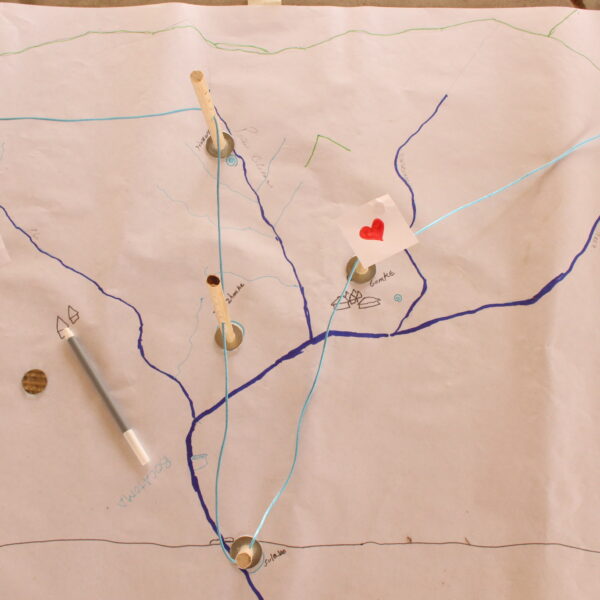

Detail of a string map of wiwa sacred territory.

Member of the wiwa community reading a locally drawn map.

String map showing the connections between parts of the landscape and points in time.