All Projects Andes Patria Invisible

Among the pieces that Apaza has worked with are embroidered costumes from negrería dances in Peru. These depict military or political figures from Peruvian history, such as Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro and Miguel Grau, figures who continue to be celebrated in national discourse. The costumes also represent Indigenous people, narratives and historic material. Negrerias originated in Afro-Peruvian communities as a way to openly subvert colonial culture and endorse their liberation from slavery.

Since then, they have been adopted by Indigenous Quechua and Aymara communities across the country. The decoration on this contemporary costume embroidery both supports and disturbs national narratives. The dances where these costumes are worn constitute a complex reimagining of time and society, and they are a form of explicit and evolving resistance to dominant culture and religion.

The museum’s contemporary embroidery collection also contains works from Puno, in the Lake Titicaca region of Peru. These costumes were made for participants in the diabladas, which are devil dances that are another example of Indigenous religious subversion and mockery of colonial rule.

Part of diablo costume consisting of a double design of dragons Am2002,10.1.e ©Trustees of the British Museum

For the people who work in the mines of Puno, this underground domain represents the opposite of what God and Christ represent, as they believe it belongs to the devil. In this region, these devil dances take place as a means to pay homage to the devil, who is viewed as a heartless overseer who can appear as a Spanish soldier, a rich mine owner or a gringo cowboy. The dances attempt to appease this figure and the forces he represents. However, at the same time, Christian missionaries disavowed Indigenous religions in the Americas as demonic belief, and so this devil Supay and his wife La Loca are also associated with Pachamama, the Indigenous earth goddess, who holds powers of fertility. In this way, the diabladas were integrated into ancestral agricultural ceremonies that have their inception before the Spanish conquest.

Embroidered Kene skirt Am1983,29.2 ©Trustees of the British Museum

The Shipibo-Konibo embroidery in the collection is predominantly kené, an ancestral design that maps the forests, waters and fauna of the riverine region of Ucayali in the Peruvian Amazon. Traditionally, only women are able create kené, interpreting the designs from their dreams and imagination. While Shipibo art is now known for its close connections with the tourist and folkloric market in Peru, the design also speaks to important pan-Amazonian philosophies, in which societal harmony is based on the spiritual and physical well-being of all aspects of the natural world, that is, people and the complex ecosystem they inhabit.

Apaza’s multidisciplinary practice is a critique of dominant national narratives in Peru, and in particular the ways in which these are transmitted in the public school system. However, her criticality is channeled through works that demonstrate the intimate and subjective experience of learning, whether that be through text or through engagement with objects. In particular, she explores her ability to learn as part of the process of making art; she learns by engaging with her ancestral practice.

In terms of Apaza’s work with the Museum’s Peruvian embroidered dance costumes, it is interesting to consider the performances for which they were made. Provocative costumes such as these were and continue to be worn on significant repeated religious or secular dates.

The dances they are used for are exuberant and active in their resistance to the society and oppressors they mock. These performative arts, such as the devil dances of the miners in Puno, Peru, are associated with predominantly male communities and take over the streets for a few days a year. This is in contrast to the process of embroidering the costumes and making the masks, which takes an entire year and comes at considerable financial cost to participants. There are devil masks from Latin America in museums internationally, and certain mask makers have achieved fame as artists. Pertinently, these are mostly men.

Nereida Apaza studying the contemporary textile collection. ©Trustees of the British Museum

By contrast, much of the embroidery work on these costumes is done by women, and embroidery in Latin America is popularly known as a women’s craft practice. Unlike Shipibo-Konibo kené, the complexity attributed to the carnivals themselves is not considered to be embedded in the embroidery itself. Apaza’s work is an example of the intellectuality and contemplation involved in embroidery as ancestral practice. While her work is critical of contemporary Peruvian politics and social issues, her art goes beyond straightforward activism. The intimacy and personal experience expressed in her work are a subtle reminder that, in the face of marginalisation, intellectuality and creativity can supplement the knowledge and narratives that are handed down to us. In her repeated images of the heroes of Peruvian history, she is reflexive about the responsibility of an artist towards her audience, as well as towards the larger society she lives in.

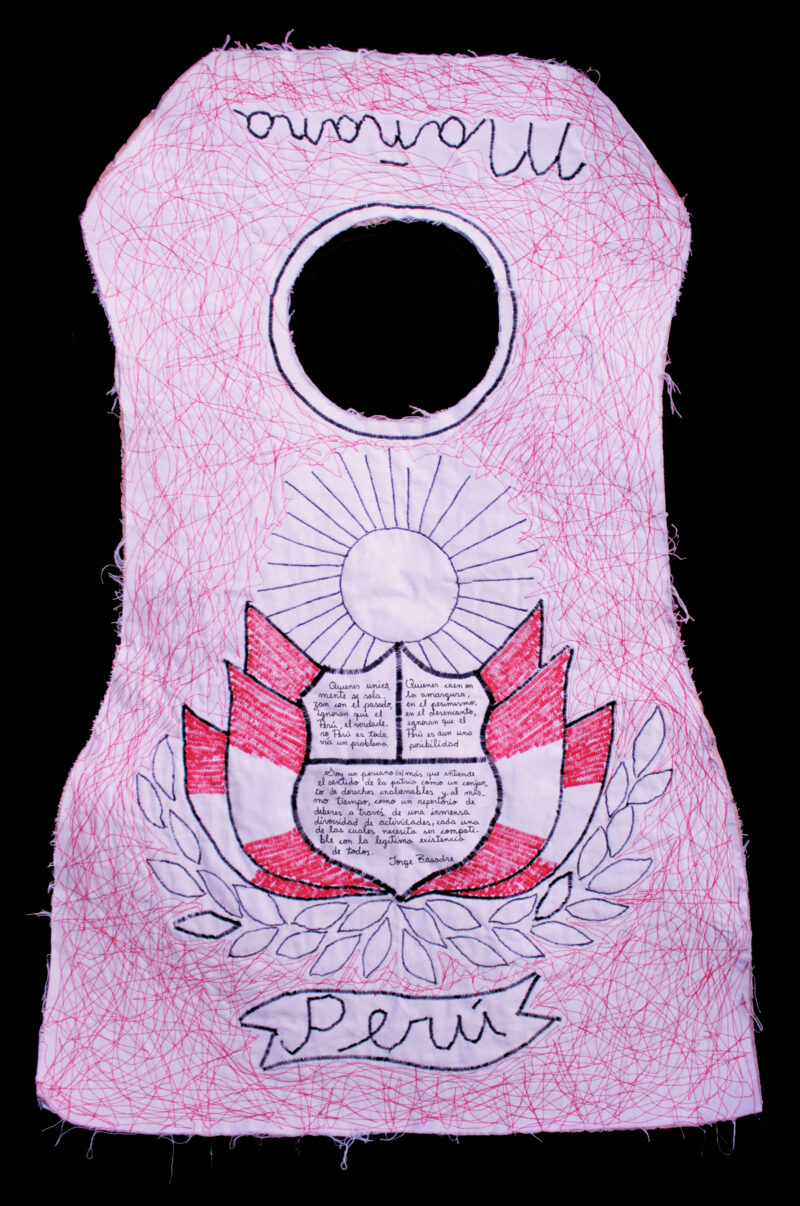

Mañana

This work replicates the shape of negrería dance bibs, which are commonly embroidered with significant figures and events from Peruvian history. Apaza has embroidered the outline of the shape of the Peruvian coat of arms onto the front of the bib, but it is empty of the symbols traditionally inserted into each central compartment. In their place, Apaza embroided a fragment of the artwork “Peru: Problemas y posibilidades” by the Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre, which focuses on the political corruption of contemporary Peru. The tangled red lines surrounding the emblem mimic the colour of the national flag, but they also reference blood. The reference to blood can be understood as relating to the generations of people who have formed Peruvian history, but it can also point to the cost of political violence.

Presidential Message, Nereida Apaza Mamani (2019) © Trustees of the British Museum

The back (neck) of the bib reads mañana (tomorrow) and is a homage to the Peruvian art activist Juan Javier Salazar, whose project using “Peru: pais del mañana” as a title criticised the nation’s hopes for reform in the future, although these have been put on indefinite hold. Not only is Apaza’s work an example of politicised ancestral practice (in this case embroidery), it also moves beyond traditional political art to include aspects of personal experience. The rough un-hemmed edges of the bib reference those of the dance bibs in the collection, which Apaza has drawn on in terms of line and composition. While the reinforcement of her bib has been made from hardened newspaper, a technique also used by dance costume embroiderers, the bib’s front-facing material is plain calico. This is the material used in the Museum’s storage to wrap the many textile works. In this way, the bib embodies the artist’s experience of historic works and their current context in museum storage.

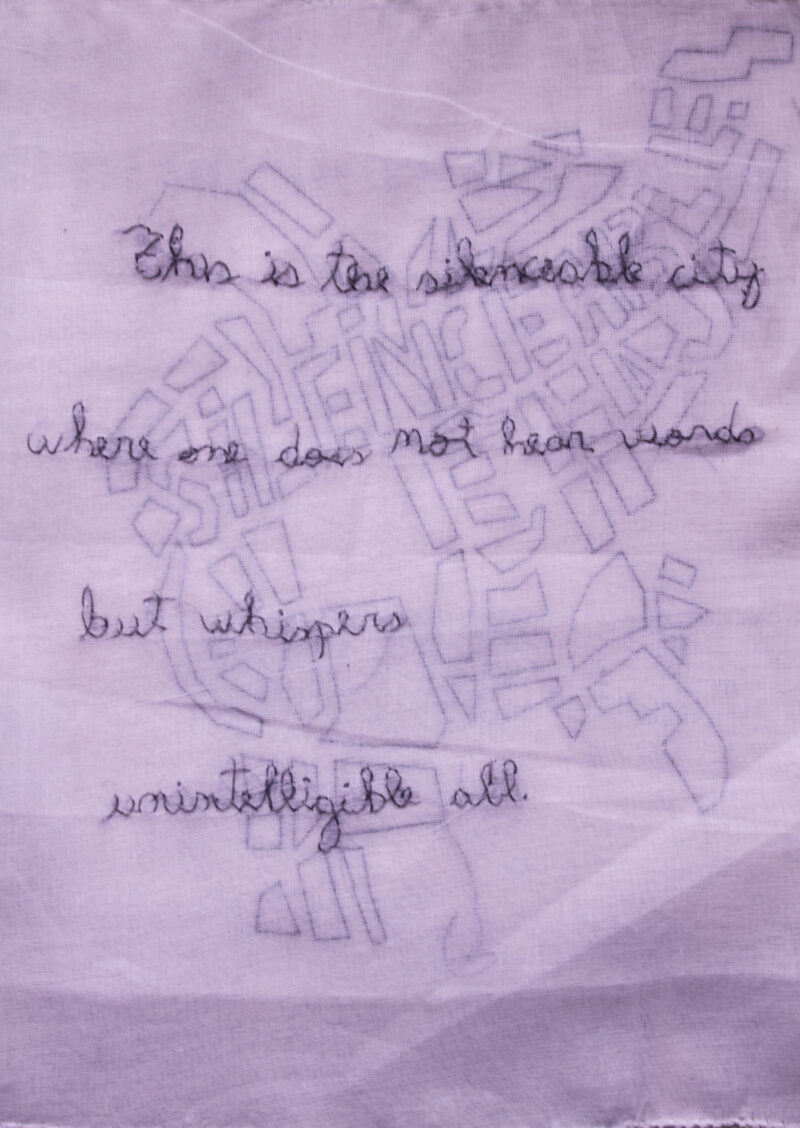

Artwork by Nereida Apaza inspired by the London "A to Z" mapbook ©SDCELAR

Apaza’s iteration of the London street map ‘A to Z’ is an embroidered textile that mimics a Peruvian school exercise book. The design on the front replicates the exercise books distributed free of charge by the government. The book contains poems written by Apaza during her stay in London and embroidered onto pages made from materials that reference those used in the British Museum’s textile storage. The colours and materials that she has employed make the content difficult to decipher. The viewer is forced to come close to the pages, and even touch them, to make out some of the phrases and images. In this way, the work obliges the audience to take the place of the artist, as this close observation and contemplation mirrors both Apaza’s study of the collection, and the time and reflexivity involved in embroidering the work.

Nereida Apaza explores the Pre-Columbian collection from Perú ©SDCELAR

The use of materials that mimic the wrapped textiles in storage alludes to the context of the museum collection. Furthermore, the idea of enveloping and wrapping connotes concepts of exteriority and interiority. Here, we might read a parallel between these concepts in terms of object/storage space and the artist’s personal experiences of navigating unfamiliar surroundings in London.

The aim of the collections projects in the Santo Domingo Centre is to create access to objects that are not on display to the public. Although works in storage are open to the public on request, they are most commonly accessed by researchers from universities, who have the funding to conduct international fieldwork. The Centre aims to promote collections engagement by a wider intellectual and creative audience.

Apaza’s project, ‘Patria Invisible’, shows how historical material and images from the past can be critically incorporated into contemporary practice. Artists such as Apaza manifest complex and challenging narratives, and the reception of her work will accommodate multiple points of view. Furthermore, the Centre considers it important to use the Museum’s collections to move beyond the study of past manifestations of ancestral, local or marginalised art forms to support the ways that they continue to evolve.