Nuestra experiencia del tiempo es fluida en lugar de fija, relativa no absoluta, y se percibe a través de las experiencias de la vida en lugar del sistema solar. Las sociedades a menudo usan los movimientos de los planetas y las estrellas para medir y explicar el tiempo, pero hay variaciones radicales en estos métodos entre las culturas. Esta exposición trata sobre la Amazonía y la forma en que ciertas comunidades allí construyen y viven el tiempo y su relación con los paisajes físicos y espirituales. Las obras que crean y las narraciones que cuentan exponen la fantasía del tiempo cuantificado y exploran las muchas formas en que las personas experimentan el tiempo y, por lo tanto, cómo consideran el pasado, el presente y el futuro.

Los museos de antropología a menudo muestran el desarrollo cultural y el cambio utilizando las estructuras tradicionales del tiempo occidental. De esta manera, la historia se presenta como lineal y acumulativa, a pesar de que las colecciones en exhibición incorporan historias individuales complejas y de varias capas. Los museos también a menudo indican áreas culturales usando mapas estándares, aunque algunas de las culturas que representan conciben el lugar donde viven. Esta exposición explora las formas alternativas de pensar sobre el tiempo y la ubicación, y cuestiona el valor de usar el tiempo occidental y las estructuras espaciales para representar la experiencia humana.

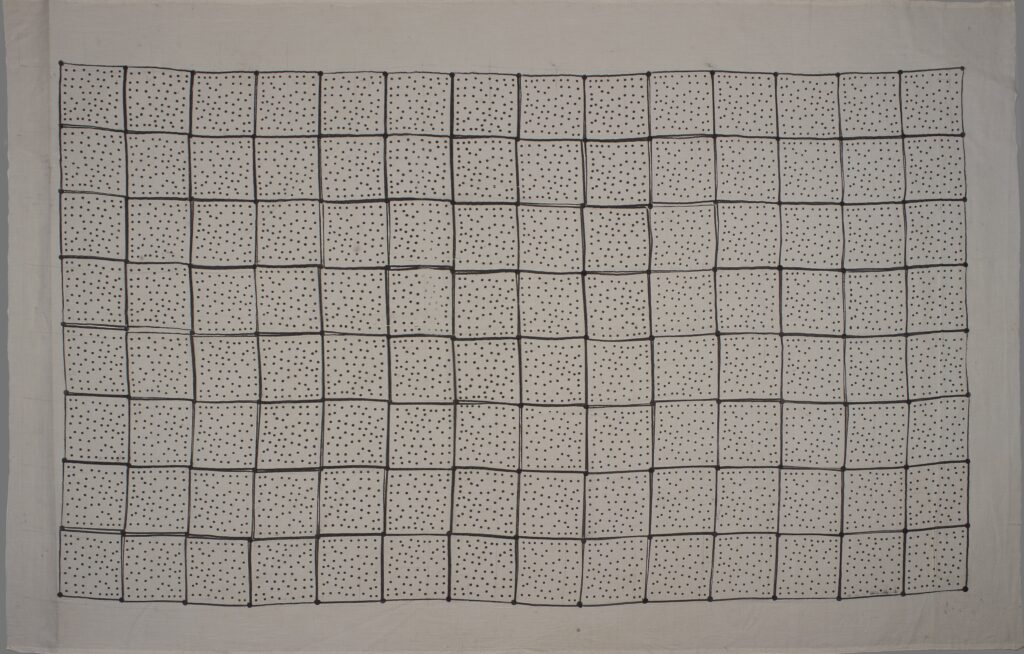

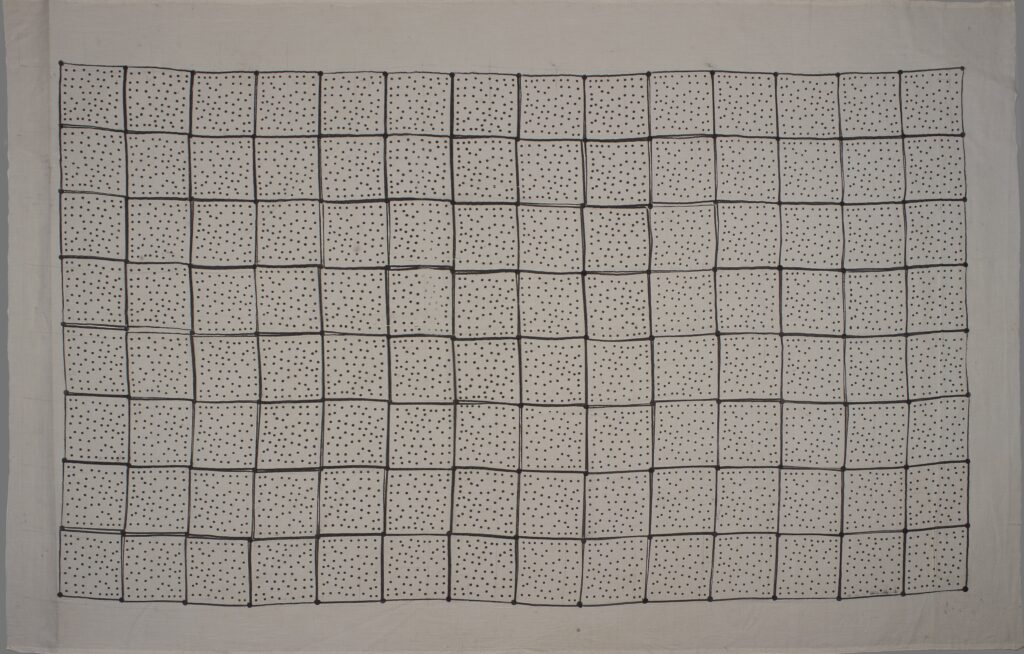

Shitikari – Starscape

Sheroanawe Hakiihiwe

2019

impreso sobre algodón

Am2019,2016.1

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

“El cielo es grande y las estrellas están ordenadas en una estructura. Por la noche, cuando hay nubes, puedes ver las estrellas en los espacios entre ellas».

Sheroanawe Hakiihiwe

Sheroanawe se refiere a la tela de algodón que ha usado para crear esta obra de arte que, como las nubes, es efímera y diáfana. Las constelaciones de estrellas en este trabajo están delimitadas por una serie de cuadrados que enfatizan el orden cosmológico ancestral yanomami. En la cosmología yanomami, una serpiente cósmica gigante cubierta de manchas encapsula el universo: el pasado, el presente y el futuro. Este trabajo evoca la experiencia individual de mirar el cielo nocturno y de esta manera innova los diseños tradicionales Yanomami. Estos diseños, aunque abstractos y esquemáticos, son mapas de la palabra vivida y espiritual.

Shitikari – Starscape

Sheroanawe Hakiihiwe

2019

impreso sobre algodón

Am2019,2016.1

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Esta cuadrícula poblada de puntos es una representación del cielo nocturno del artista yanomami Sheroanawe Hakiihiwe. Hace referencia a la serpiente cósmica gigante punteada que contiene el universo, su pasado, presente y futuro.

Sheroanawe actualmente no puede viajar fuera de Venezuela donde vive, debido a las tensiones políticas. Este es solo un ejemplo de cómo los procesos políticos pueden obstaculizar la inclusión de las perspectivas indígenas del pasado y el orden mundial en la arena internacional.

Kené. Diseño vivo

Artista desconocido

Vasija de cerámica

Am.8844

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Ciertas mujeres de la comunidad Shipibo-Konibo de la Amazonía peruana pueden interpretar el kené en forma material, por medio de un diseño que mapea las aguas, árboles y animales interconectados que conforman el sistema fluvial Ucayali de donde provienen. Estos diseños también representan las venas en las hojas del bosque y las constelaciones de estrellas que están asociadas con el tiempo mitológico. Estas mujeres sacan los diseños de sus sueños y los impregnan de una canción ancestral y fuerza.

Kené representa y encarna a la anaconda Ronin desde el tiempo primordial. Su piel viva mapea el entorno natural en la región Ucayali de la Amazonía para que, si su poder llegase a morir, toda la vida en el bosque, los animales, los peces y los árboles, también morirían.

Al igual que con el consumo de plantas con energía, como la Ayahuasca, el kené a menudo se describe como una experiencia multisensorial. Si bien son los hombres de esta comunidad quienes practican la curación con plantas poderosas, tradicionalmente solo las mujeres pueden soñar y crear Kené.

Kené. Diseño vivo

Artista desconocido

Vasija de cerámica

Am.8844

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Esta olla fue recolectada del pueblo Shipibo-Konibo en la década de 1930. El diseño pintado que tradicionalmente está hecho solo por mujeres se llama kene. Representa la anaconda ancestral y su encarnación en los ríos y bosques del Ucayali de donde proviene el pueblo Shipibo-Konibo.

Desde que se recolectó este objeto, ha habido una migración significativa de las comunidades Shipibo a la ciudad cercana, Pucallpa, así como a Lima. La energía primordial asociada con la fabricación de kene brinda a las mujeres contemporáneas de la diáspora Shipibo-Konibo la inspiración para continuar creando kene, venderlo y compartirlo con la comunidad global.

Universo, contenido

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1905

canasta hecha con fibras vegetales

Am1905, 0216.107

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Para las personas de Murui-Muina (Witoto), las canastas son símbolos del conocimiento que poseen las mujeres que las fabrican. Las canastas bien confeccionadas y bien tejidas son el trabajo de mujeres que tienen cuidado de no perder su conocimiento, mientras que las canastas más sueltas y menos meticulosamente tejidas representan a las fabricantes que no mantienen sus tradiciones.

Como contenedores, las canastas también representan el marco del universo para muchos pueblos amazónicos. De manera similar a lxs yanomami, los recipientes son microcosmos de una entidad espacial y temporal que contiene todas las cosas.

Estas canastas son bastante pequeñas y probablemente se usaron para recolectar hojas de coca. Se usaron canastas similares más grandes para transportar grandes bultos pesados, como la yuca sin procesar.

Universo, contenido

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1905

canasta hecha con fibras vegetales

Am1905, 0216.107

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estas canastas, las cuales probablemente fueron utilizadas para transportar hojas de coca, fueron hechas por la gente Murui-Muina en La Chorrera. Para lxs Murui-Muina, el tejido de canastas es un símbolo de la memoria cultural y la importancia de la transmisión del conocimiento. Estos objetos son particularmente conmovedores, dado que fueron recolectados durante el genocidio del auge del caucho, lo que llevo a la casi aniquilación de los Murui Muina y otros pueblos que vivían a lo largo del Igaraparana. La muerte y el desplazamiento destruyeron muchas de sus prácticas culturales y sistemas de conocimiento.

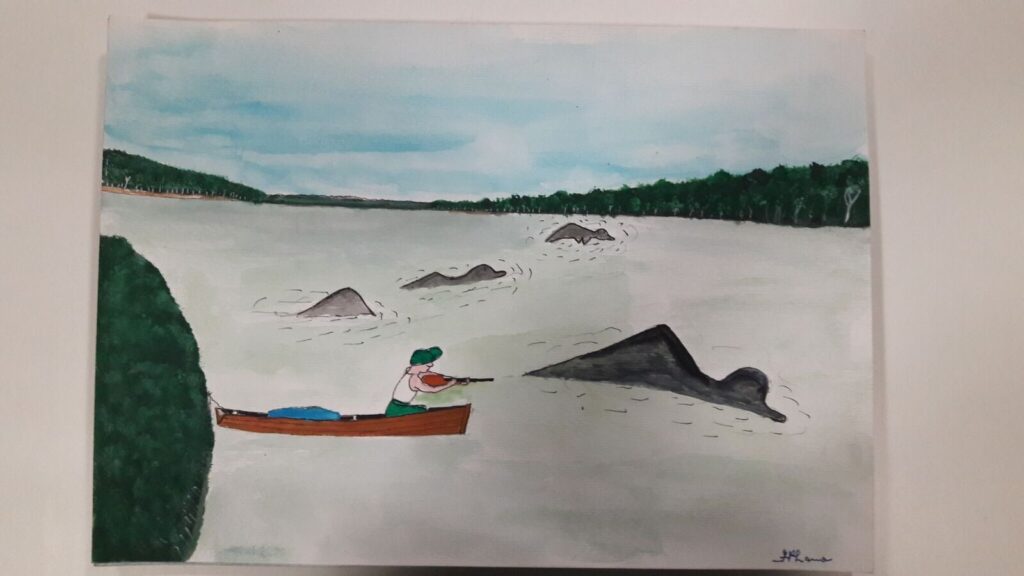

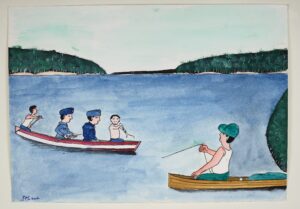

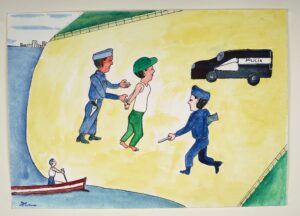

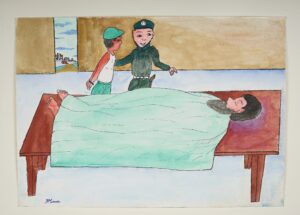

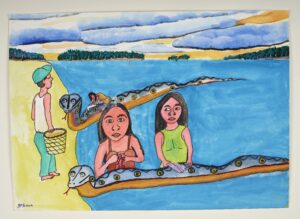

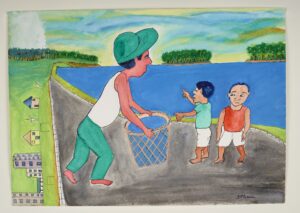

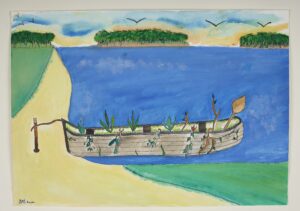

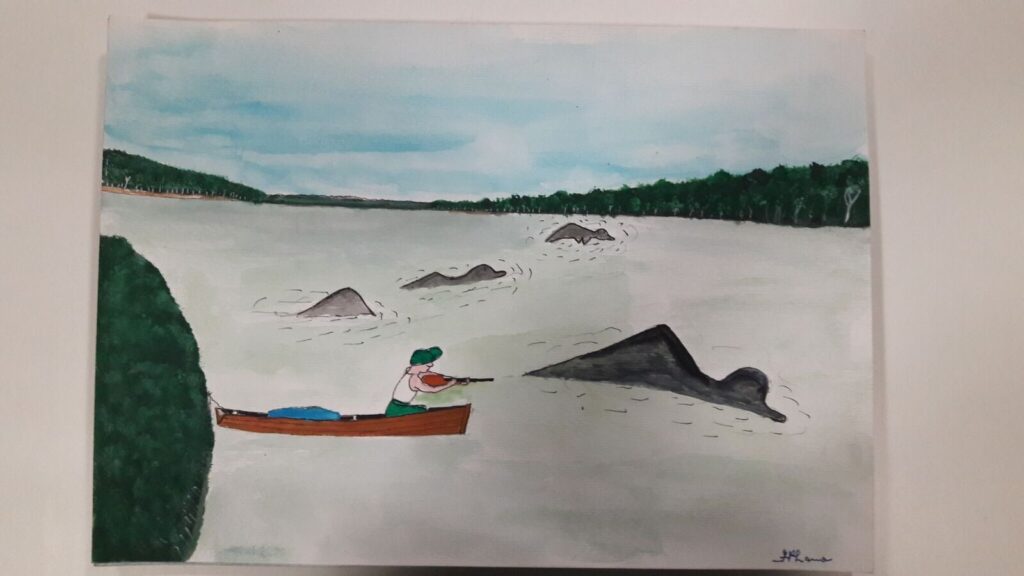

Gente pez

Felicinao Lana

2019

Acuarela sobre papel

Según las narraciones orales de los Tukano Orientales del Río Negro Superior en el Amazonas, la humanidad se originó con el viaje de la serpiente-canoa de la transformación. El viaje comienza en el Lago de la Leche y llega a las cascadas de la región de Uaupes. En el camino, la canoa visita las Casas de Transformación, donde estas primeras personas adquieren bienes y conocimiento, y finalmente se convierten en las Personas de Transformación, como los Tukano se refieren a sí mismos.

Estas acuarelas fueron pintadas por el artista desana llamado Feliciano Lana. El describe historias ancestrales que se transmitieron oralmente a lo largo del tiempo, pero que también contienen prácticas y temas contemporáneos. Explican los orígenes del conocimiento ictiológico mientras se centran en las personas y los animales que pueden transformarse de una cosa a otra. La repetición de historias de origen en el tiempo contemporáneo ilustra la comprensión de la comunidad sobre la flexibilidad en la experiencia del tiempo. Este estilo narrativo desafía la estructura lineal acumulativa que las filosofías occidentales dominantes usan para vincular un evento en el pasado a uno en el presente o en el futuro.

Gente pez

Felicinao Lana

2019

Acuarela sobre papel

Estas pinturas muestran los orígenes mitológicos de los tukanos que viven cerca del río Uaupes en la Amazonía brasileña y colombiana. En el primer episodio, se muestra a un hombre disparando a un delfín. Esta es una referencia a la matanza de delfines de río porque destruyen las redes de pesca, pero también porque al ser considerados criaturas metamorfas, se cree que los delfines se disfrazan de humanos para seducir y, a veces, cometer violaciones. Esta es tanto una historia de origen como una narrativa contemporánea que continúa desarrollándose.

Más adelante en la secuencia de la acuarela, el delfín aparece como un hombre muerto en la estación de policía, y su atacante fue arrestado por asesinato. Aquí la incomprensión de las autoridades representa las filosofías culturales dominantes que no reconocen los poderes metamorfos del delfín.

Dientes de delfín

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1925

fibras vegetales tejidas y dientes de delfín de río (Inia geoffreensis)

Am1925,0704.9

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Los delfines del río Amazonas ejercen el poder del amor y el sexo y, como tal, sus dientes pueden ser archivados y utilizados por especialistas en rituales para crear magia de amor. Los delfines también son metamorfos y pueden transformarse en humanos. Luego frecuentan bares y fiestas junto al río para seducir a las personas que viven allí.

Los dientes de delfín tienen un poder que puede ser peligroso si no es aprovechado por personas que tienen el conocimiento y que pueden manipular la transformación. Estas personas usan habilidades ancestrales para moverse a través del tiempo y los mundos espirituales, construyendo relaciones con los seres que los habitan.

Dientes de delfín

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1925

fibras vegetales tejidas y dientes de delfín de río (Inia geoffreensis)

Am1925,0704.9

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estos dientes se recogen para aprovechar los poderes vivos de los animales de los que se toman. Los delfines son metamorfos asociados con la sexualidad. Aunque los habitantes metamorfos del río son un fenómeno pan-amazónico, para los Murui-Muina en La Chorrera, los delfines se disfrazan de personas blancas: bien vestidos, perfumados y ricos. Los delfines están asociados con la adquisición y la codicia de los extranjeros en la Amazonía, así como con las enfermedades extranjeras que son producto del contacto cultural.

Los delfines viven en los grandes ríos de la Amazonía. Las narrativas y el conocimiento asociado con los delfines han llegado a las comunidades que se retiran de estos grandes ríos (como los de La Chorrera de donde proviene este collar) como resultado del movimiento de personas e ideas durante el auge del caucho. Este collar habría sido un objeto nuevo cuando se recogió en la década de 1920.

Este collar vivo encarna no solo el poder de los delfines del río sino también un período de contacto cultural y trauma.

Cuando la palma de chontaduro madura

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1973

tela de corteza, fibra vegetal, junco

Am1973,07.15, Am1973,07.9

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

A lo largo de los afluentes del río Caqueta, en febrero/marzo de cada año, cuando el Chontaduro o la fruta de la palma de durazno madura, el mundo mítico se dramatiza y se recrea.

Estos trajes de tela de corteza se usan para los bailes de yucuna en la Amazonía colombiana. Aquí, las comunidades se preparan y finalmente realizan el baile durante dos días y noches completas. Esta actuación involucra una serie de canciones, bailes y narraciones, durante los cuales varios peces y mamíferos llegan a la maloka, un edificio que encarna la estructura del tiempo anual y diario. En este festival, lxs participantes tienen una experiencia corporal del ciclo agrícola.

Cuando la palma de chontaduro madura

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1973

tela de corteza, fibra vegetal, junco

Am1973,07.15, Am1973,07.9

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estos trajes se usan a lo largo de la Caqueta para el baile de Chontaduro que tiene lugar cuando madura la fruta de durazno. El baile recrea un momento mítico en el que los animales y los peces ingresan a la casa comunitaria o maloka. La maloka es una representación espacial del tiempo y los ciclos anuales.

Si bien ciertos otros bailes en la región son específicos de una comunidad, la ceremonia del Chontaduro es común a muchos pueblos, por lo que a menudo se practica comunalmente en malokas compartidas en Leticia, la capital de la Amazonía colombiana. Varios pueblos diferentes de la Amazonía occidental ahora viven en Leticia como resultado de los cambios sociales que han tenido lugar desde la fundación de la ciudad a mediados del siglo XIX.

Animales en transformación

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1964

tela de corteza pintada, fibras vegetales

Am64,03.19

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estos disfraces fueron usados para el baile onye o «lloroso» por personas cubeo, que son de la región de Tukano a lo largo del río Uaupes en Brasil y Colombia. Esta ceremonia de baile que dura tres días, y está destinada a convertir el dolor en alegría después de la muerte de un miembro de la comunidad. Los disfraces encarnan el espíritu del ser que representan. Son mamíferos, peces e insectos, así como versiones de transición o juveniles de animales, como larvas o huevos. Entre estos se encuentran los espíritus que pueden moverse entre las tres capas del cosmos, como los jaguares que pueden trepar a los árboles o los escarabajos de estiércol que consumen y entierran sustancias muertas. La importancia de estos espíritus marca la ceremonia como una de transición entre los mundos de los vivos y los muertos, así como los roles de renacimiento y regeneración a lo largo del tiempo.

Animales en transformación

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1964

tela de corteza pintada, fibras vegetales

Am64,03.19

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estas largas máscaras fueron utilizadas por el pueblo cubeo, que vive a lo largo del río Vaupés en Brasil y Colombia. Después de la muerte de un miembro de la comunidad, se llevaron a cabo bailes de duelo, llamados onye, y las máscaras se usaron para disfrazar a los bailarines como animales e insectos o huevos y larvas. El baile representa y promulga las relaciones entre las personas y los espíritus en el complejo de tiempo y espacio cubeo de múltiples capas.

Esta ceremonia fue suprimida en la década de 1940 por los misioneros católicos, que habían llegado a los Vaupés en muchos casos para mejorar los problemas sociales causados por la extracción de goma, pero que se opusieron a prácticas como estas, ya que las consideraban una forma de adoración al demonio. Desde la incorporación de la región al estado colombiano en la década de 1970, las ONG y otras organizaciones de revitalización cultural han intentado revivir los bailes onye, pero actualmente ninguna comunidad los practica.

Capa para sanador

artista desconocido

elaborada antes de 1927

plumas de guacamaya, corteza

Am1927,0217.1

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

En la Amazonía existen múltiples formas de convertirse en una persona que puede adquirir la capacidad de moverse a través de las dimensiones espaciales y el tiempo, y así sanar y dar forma a la experiencia del mundo de una comunidad. En muchos casos, un padre o mentor puede transmitir poderes espirituales, un proceso que a menudo implica experimentar intensas experiencias, incluidos actos de agresión, para crear asociaciones con espíritus ancestrales. Esta transformación en un especialista de rituales, así como las transformaciones posteriores requeridas para la transición entre los mundos del espacio y el tiempo, a menudo implica estados de sueño y plantas poderosas.

Esta capa fue usada por un sanador Macuxi de lo que ahora se conoce como Guyana. Las plumas habrían imbuido al usuario con los espíritus de los pájaros de los que vinieron, y se habrían usado para ceremonias especiales.

Capa para sanador

artista desconocido

elaborada antes de 1927

plumas de guacamaya, corteza

Am1927,0217.1

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Esta capa de plumas pertenecía a un curandero macuxi o Piatzan que vivia en las sabanas del sur de Guyana. Piatzan puede moverse entre tres planos superpuestos que convergen en el horizonte. Los seres que viven en estos planos periódicamente a espíritus humanos, los cuales pueden llevar a su muerte mortal. Piatzan puede sanar personas al batallar e involucrar con estos seres.

Al igual que otras partes de la Amazonía, el territorio habitado por los Macuxi y otros grupos indígenas se ha utilizado para proyectos extractivos como la extracción de caucho y la ganadería. Muchos de estos involucraron el desplazamiento de personas a través de redadas de esclavos. Se accede a los tres planos temporales y espaciales a través de los cuales puede viajar el Piatzan en partes especiales del paisaje. La transmisión de las habilidades del Piatzan también depende de transmitir este conocimiento esotérico a las nuevas generaciones. El desplazamiento de la gente de Macuxi ha dificultado el acceso y la transmisión del conocimiento de Piatzan dentro de la comunidad. Esta es una de las formas en que las relaciones indígenas culturalmente específicas con la experiencia y la gestión del tiempo se ven afectadas por los proyectos de colonización.

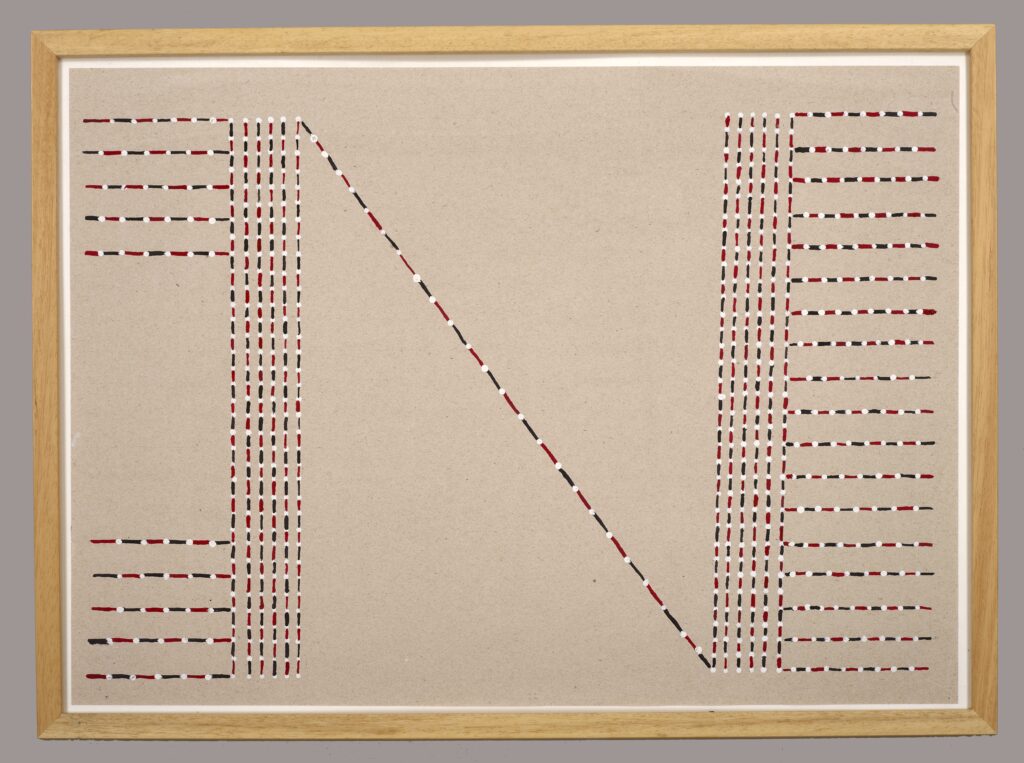

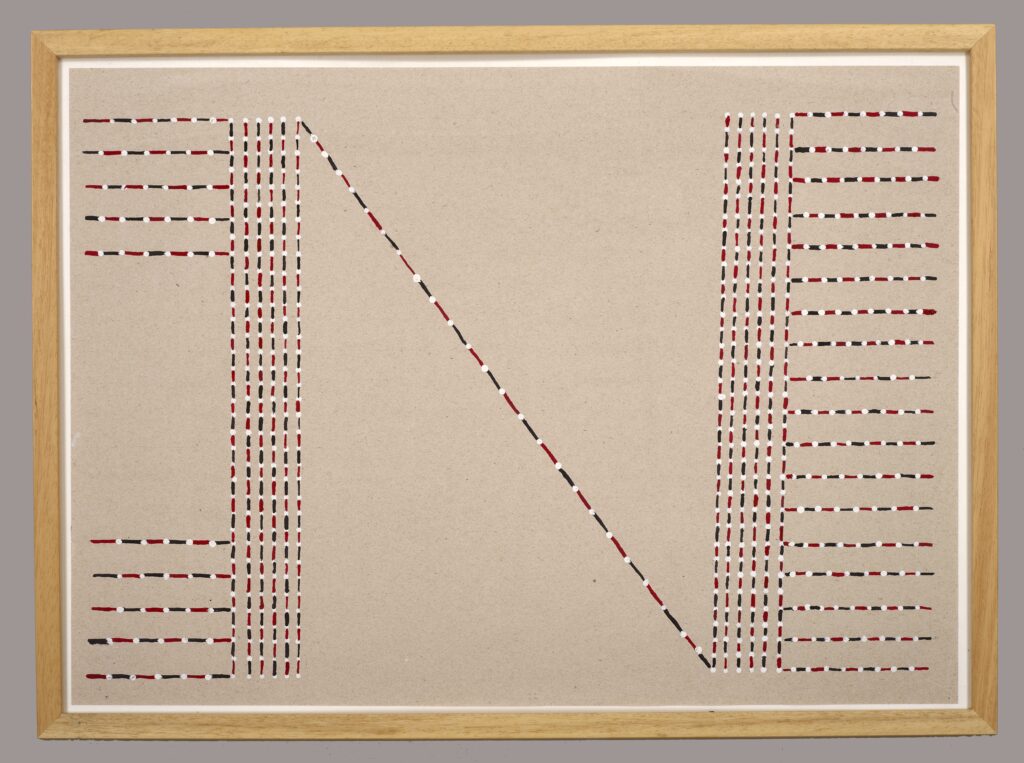

Huwe Moshi – Serpiente de transformación

Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe

2019

acrilico pintado sobre papel

Am2019,2016.2

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

En esta pintura, los colores simples de la serpiente de coral – negro, rojo y blanco – se transmutan en formas abstractas, volviéndose geométricas, diagonales y horizontales. La falta de realismo en la representación de esta figura evoca los estados de sueño asociados con las ceremonias de transformación que existen fuera de las experiencias ordinarias del espacio-tiempo.

Las serpientes de coral son venenosas y, en su capacidad de moverse entre el agua y la tierra, a veces se asocian con practicantes de rituales y hechicería oscura. Esta pintura es de la serie HuweMoshi, donde Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe usa esta serpiente para referirse a los poderes transformadores asociados con las personas míticas en la comunidad yanomami.

Huwe Moshi – Serpiente de transformación

Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe

2019

acrilico pintado sobre papel

Am2019,2016.2

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

En su ilustración de la serpiente de coral venenosa, Sheroanawe Hakiihiwe convierte sus curvas fluidas en líneas ortogonales. La serpiente es reconocible por su característica secuencia de colores repetidos de negro, blanco y rojo. La pintura evoca los poderes de transformación de los seres en la mitología de origen yanomami.Aunque el artista recurre y representa temas ancestrales en esta pintura, también se involucra con movimientos artísticos contemporáneos globales como el expresionismo abstracto. De esta manera, la pintura desmantela suposiciones sobre la incompatibilidad del conocimiento tradicional local con la cultura global dominante.

Dientes de jaguar

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1925

dientes de jaguar, cuentas de vidrio

Am1925,0704.5

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Para lxs Murui-Muina, los poderes depredadores de los jaguares pueden aprovecharse y hacerse útiles para los humanos a fin de administrar el tiempo y el espacio en el universo eterno. El uso de un collar de dientes de jaguar dotó a sus usuarios del poder del jaguar y de los líderes ancestrales de la comunidad.

El jaguar es un animal de poder, y los espíritus de los guerreros y cazadores de la comunidad, tanto actuales como primordiales, están presentes dentro de él. Cuando un/a líder usa un collar de diente de jaguar, a él/ella se le infunde las habilidades y el conocimiento del mundo espiritual, y puede ver a través de los ojos de este depredador.

Dientes de jaguar

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1925

dientes de jaguar, cuentas de vidrio

Am1925,0704.5

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estos dientes de jaguar eran propiedad de aquellxs que tenían la capacidad de aprovechar el poder espiritual de sus antepasados. Los collares de dientes amazónicos fueron recolectados como objetos científicos por los primerxs antropólogxs y otrxs exploradorxs desde el siglo XIX en adelante. Pero para las personas de quienes provienen, estos collares contienen espíritus ancestrales. La llegada de estxs coleccionistas y su interés en tales objetos coincide con proyectos extractivos, como la extracción de caucho por parte de colonos blancos.

La extracción forzada extranjera de recursos naturales continúa teniendo un impacto en la ecología y la sociedad amazónica hasta el presente. Estos procesos amenazan la relación de las personas con una tierra que encarna su historia cultural. Este proceso ve una fractura de los vínculos entre pasado, presente y futuro.

Medicina de tabaco

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1905

calabaza, fibras vegetales

Am1905,0216.101

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Esta nuez fue utilizada por lxs Murui-Muina para contener y transportar ambil, el cual es una resina hecha de tabaco. Esta resina se hace secando las hojas de tabaco, mezclándolas con agua o una bebida fermentada, y luego calentando la mezcla hasta que esté espesa y fuerte. El ambil se extrae con un palo para masticarlo periódicamente.

Para las personas en la Amazonía, el tabaco es una sustancia poderosa con la capacidad de curar al reconectar a las personas con su linaje y tierra ancestral. El tabaco se puede inhalar, fumar, comer y aplicar al cuerpo. Ayuda a lxs miembros de la comunidad a mantenerse alerta durante las noches ceremoniales, reforzando un eterno sentido de pertenencia a la comunidad.

Hay dos efectos de comer o inhalar tabaco durante las ceremonias de curación. Primero, el cuerpo rechaza la amargura de la planta, produciendo náuseas y mareos. De esta manera, el tabaco limpia el cuerpo de contaminantes externos y lo prepara para la curación. Segundo, el tabaco agudiza los sentidos, haciendo que los sonidos, los olores y los aspectos visuales de la ceremonia se fusionen con el cuerpo y la mente.

Medicina de tabaco

artista desconocido

elaborado antes de 1905

calabaza, fibras vegetales

Am1905,0216.101

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Estas nueces en algún momento contenían ambil, una fuerte resina de tabaco comestible. Ya no son hechas por las personas en La Chorrera, donde eran recolectadas durante el principio de la década de 1900. Actualmente se sustituyó con botellas de plástico. El tabaco es una herramienta ancestral utilizada para manejar la experiencia corporal del tiempo y es masticada en todas las negociaciones fuera de los grupos, para que los usuarios puedan hablar con claridad. Diferente al uso de oras plantas poderosas en esto y otras partes del Amazonas, tal como las hojas de coca, masticar tabaco de ambil no está restringido a un género: ambos hombres y mujeres mastican tabaco. La nuez con la figura humana tallada en él es usado por hombres; tiene una pequeña entrada y la resina se puede extraer con una pequeña rama. La otra sencilla nuez es para las mujeres; tiene un agujero un poco más grande, ya que las mujeres usan sus dedos para extraer el tabaco.

Corona color mambe

elaborada antes de 1905

plumas, corteza

Am1905,0216.7 (a)

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Las plumas utilizadas para hacer estas coronas no son elegidas simplemente por su belleza. Cada pájaro y color son una representación de las poderosas fuerzas naturales. Por ejemplo, algunas de las coronas combinan tonos de azul y verde produciendo un turquesa con multi-capas. Este color representa el mundo en sus orígenes y es asociado con mambe, el cual son una hoja de coca en polvo y activada con limón que las personas del Amazonía mastican para reunir sus pensamientos y hablar sabiamente. El uso de esta poderosa planta sostiene y reproduce el orden del universo.

El consumo de la hoja de coca activada fortalece el material y las relaciones intelectuales entre comunidades y su territorio ancestral a través del tiempo.

Corona color mambe

elaborada antes de 1905

plumas, corteza

Am1905,0216.7 (a)

© Fideicomisarios del Museo Británico

Esta corona tiene una pequeña capa de plumas al frente de un círculo de palma tejido y pudo haberse usado en ceremonias antes y alrededor del tiempo que fue adquirido de La Chorrera en 1903. Esta fue la altura de atrocidades cometida durante el auge de caucho. Durante este periodo, la Compañía Amazona Peruana instigó el asesinato, violación y tortura de grupos indígenas en el oeste del Amazonas para poder aumentar la producción de caucho que fue exportada internacionalmente por carros y maquinas.

Miembros jóvenes de los grupos indígenas de La Chorrera no reconocen las coronas como estas como parte de su tradición o historia cultural. Esto es una consecuencia del auge de goma, durante y después de lo cual estas coronas no fueron producidas o usadas, como las ceremonias en las que en las que se usaban a no se hacían. Esta corona proveía un importante recurso para las comunidades cuya memoria cultural fue fracturada por el genocidio del auge del caucho.