- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

Contact Zone I

The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

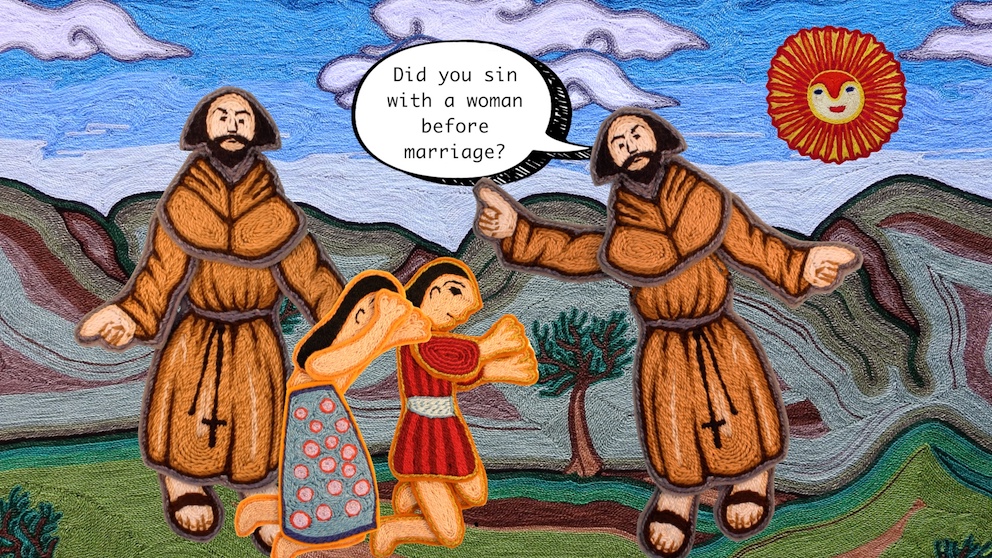

The evangelisation of intimate life happened over more than three centuries of colonialism as Catholic missionaries and colonial legislation imposed a European Christian set of morals and values on Indigenous peoples.

Lives were changed forever as colonisers used violence, coercion and religious doctrine to force or shame tribes and settled communities into abandoning their millenarian practices, adopting the institution of marriage and worshiping Christian gods.

For the Franciscan missionaries who visited the Sierra Madre Occidental this was a difficult task. Wixaritari held vehemently to their ways and for more than a century were largely resistant to the persuasions of missionaries. Their mountainous terrain and dispersed living arrangements helped them in this quest and protected them from constant invasion.

Arrival of the Spanish. 'Ukari Wa’utiska' animated film by Susie Vickery

Arrival of the Spanish. 'Ukari Wa’utiska' animated film by Susie Vickery

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

However, documentation of mass marriage ceremonies in Santa Catarina and San Sebastián during the 17th and 18th Centuries, obligatory attendance at church services and the widespread use of confessionary books over several generations, eventually instilled a new set of moral ideas in their minds, although these continue to be viewed with some degree of scepticism.

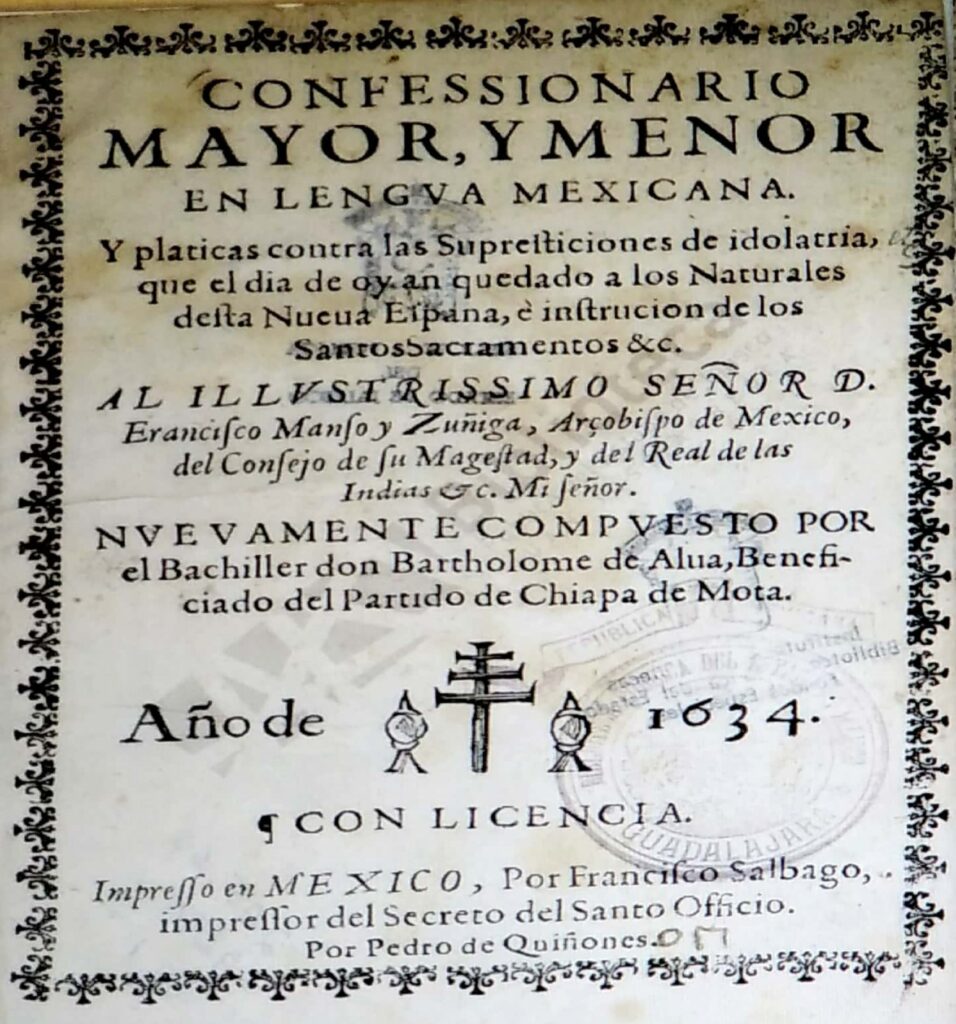

"Confessionary. Major and Minor in Mexican Language.

And talks against idolatry that today has remained with the Naturals of this New Spain and in the Holy Sacraments and commandments.

The most Illustrated gentleman D. Francisco Manso y Zuñiga, Archbishop of Mexico, on advice of his majesty and the Royalty of the Indias and My Lord.

Newly composed by Bachiller Don Bartholomé de Alva, Beneficiary of the Chiapa de Mota Party.

In the year of 1634

Printed in Mexico, by Franciso Salbago, printer of the Secrets of Saint Office, by Pedro Quijoñes

View text of image

'Confessionary in Mexican Language'

Don Bartholomé de Alva, 1634

Invasion and Ethnocide

Timeline of colonisation and evangelisation

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

The first writings we have about Wixárika people that give some indications of gendered practices are in the writings of missionaries who spent time in their communities.

Between Indigenous tribes and the Spanish Army

Tello describes the evangelisation of Huaynamota

Examples: Have you willfully aborted (a pregnancy)? | How many women have you sinned with?

Examples: Have you performed sodomy? | Aborted with poisonous drinks? | Have you lived with woman/man outside wedlock? | With how many women have you sinned? | |Have you sinned with a family member? | Have you performed bestiality?

Examples: Do you believe in an Idol and have you made offerings? | Have you drunk poison to abort (a pregnancy)? | Have you sinned with a women or a man?

Baptisms, marriage and births.

Examples: Have you married in secret or more than once? | Do you have dirty or dishonest thoughts' | Have you penetrated a woman or a man from behind? | Do you have the woman you sin with at home?

Evangelisation and documentation of economic activities.

San Andrés, Santa Catarina and San Sebastián, among other towns, adhere to the Spanish Government.

Traveller documented: commercialisation of salt, use of bow and arrow, marriage practices and dress.

Complaints from San Sebastián and San Andrés of invasions by residents of Santa Catarina. Guadalupe Ocotán complaints of neighbours from Huajimic stealing their animals. Also, Huichols are asked to wear trousers when they go to the city to sell.

Denounces (Mestizo) invasions from the Hacienda of San Juan. Residents of San Juan Peyotán denounce land invasions by San Andrés.

Land invasions from San Andrés, Tenzomopa, Nostic and San Antonio Padua. San Andrés complain of animals from San Juan Capistrano invading their land and destroying their crops.

Experiences a typhoid epidemic, maize shortage and drought. Land invasions in San Andrés, San Sebastián and Tenzompa by the Hacienda of Camotlán.

Visit to the Huichol Homelands: significant documentation of births, marital partnerships, courtship and relationships with local authorities.

Documents Huichol political structure.

Documents Huichol authorities, settlements, gendered division of labour, births, baptisms (by gender) and marriage.

Examples: Have you given in to sinful desires? | Have you spoken of indecencies? | Have you consented to sodomy? | Have you obeyed your husband in all licit requests?

In Tuxpan Wixaritari denounce the attempted invasion of Americans in El Saucillo mountains.

In San Andrés: Presbyterian missionaries steal and farm and crops.

Santa Catarina request information about the supposed sale of a field to an individual, if this rumor proves to be false they request the removal of cattle who are a threat to crops.

In San Andrés requests tiles for their land as the owner of the Hacienda at San Juan Capistrano and residents of Santa Catarina pose a threat to their properties.

Writes of newborns and mothers, Responsibilities of Wixárika men, Masculine and feminine in mythology, Corporal punishment and its use in cases of infidelity.

Tuxpan requests assistance from the state governor to develop agriculture and protect their lands.

Domingo Lázaro de Arregui was one of the first missionaries to write about Indigenous peoples in the region now occupied by Wixárika communities.

“And these Indians of this town [Colotlán] communicate with those of Guaximic and with another neighboring nation called Guaramota, people who when they want to, they are Christians and when they don’t, they are not, and this is understood when they go to doctrine”

Domingo Lázaro de Arregui, Descripción de la Nueva Galicia, 1980 (1621) 156-7.

Wixárika

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

In 1783 Pedro Trelles Villademoros described how Wixaritari from Santa Catarina and San Sebastián dressed.

‘Their costume is as if they have spent time on it, in the way of the gentility, because they bring cotton of ixtle and wool, rawhide breeches, ordinary straw hat; the one used only by married people. Those who are not [married], bring their hair loose and on the neck and throats of the feet, use many chokers of shells and beads of many colours. The maiden women wear very fine cottons, and a wrap up to the knee, with most of the chest bare: On the contrary, the married ones, cover something more this, and the feet, and do not put the work into their cottons.’

Archivo General de la Nación

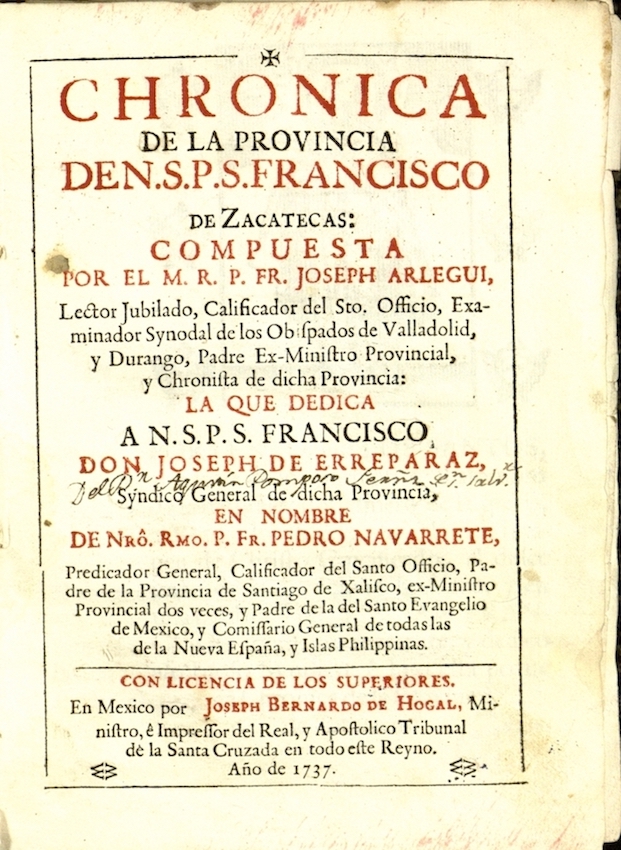

Marriage and birth practices were documented by Fray Joseph Arlegui

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

Arlegui was the first to document childbirth practices.

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

Crónica de la Provincia de N.S.P.S. Francisco de Zacatecas, 1737, José de Arlegui

Chronicle of the province of N. S.P.S Francisco of Zacatecas:

Composed Friar Joseph Arlegui, Celebrated reader, Qualified in the Saintly Duty, Sinodal examiner of the Bishopdoms of Valladolid and Durango, Father and Ex-Provincial Minister and chronicler of this province.

That is dedicated to A N.S.P.S Francisco, Don Joseph de Erreparaz, Genderal Syndicate of this Province in the name of De Nro. Rmo. P. Fa. Pedro Navarrete.

General Preacher, Qualifier of the Saintly Office, Father of the Province of Santiago of Xalisco, Ex Provinical Minister twice over and Father of the Saintly Evangel of Mexico and General Commissioner of all those of New Spain and the Philippine Islands.

With Licence of the Superiors, in Mexico by Joseph Bernardo de Hogal, Minister, Royal Printer, Tribunal of Santa Cruz Apostle for this whole Kingdom.

The year of 1737

View text of image

Fray José Arlegui chronicled birthing practices in the early 17th Century. © Digital Library AECID. CC (BY-NC-SA)

Ceremonies and Evangelisation

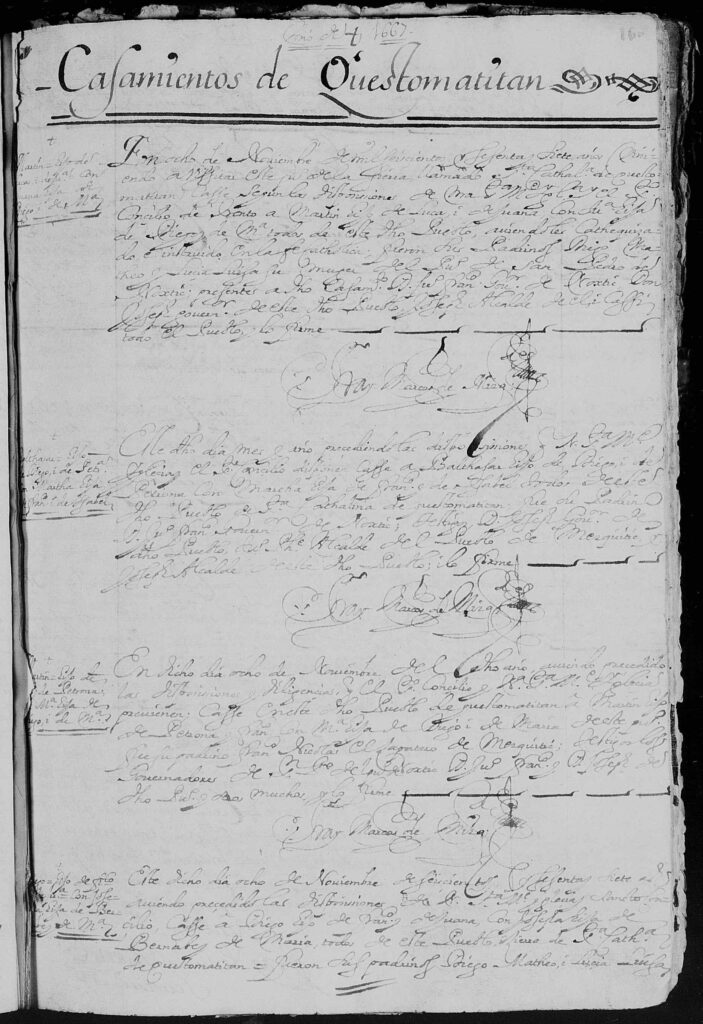

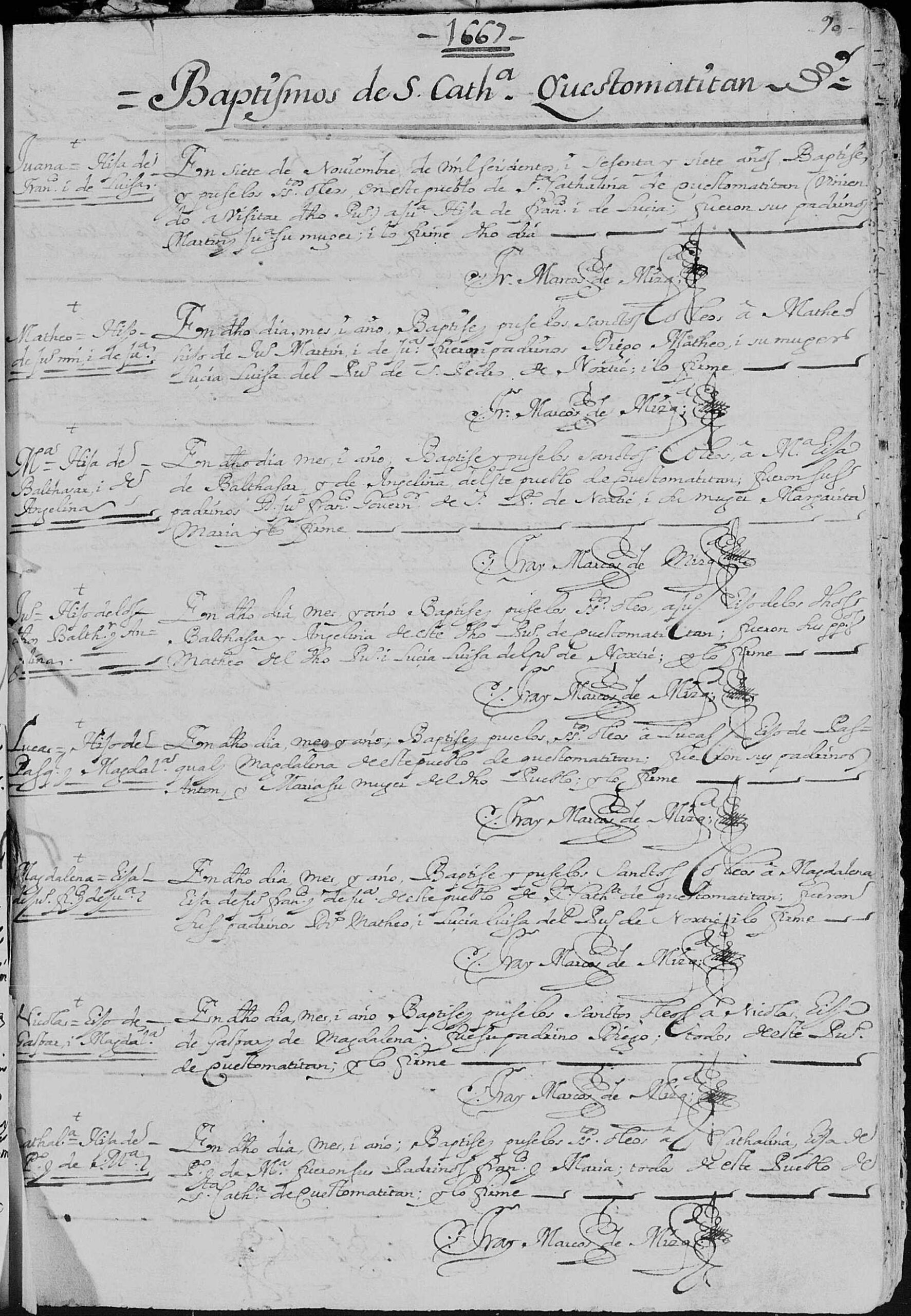

Records from 1667 suggest that Franciscan Friars lived intermittently among the Wixárika communities of Santa Catarina, San Andrés and San Sebastián.

Each of these communities experienced mass baptism and mass marriage ceremonies as the Friars travelled from village to village gathering ‘indians’, teaching the commandments and maintaining churches.

Records of mass christenings in Santa Catalina Questomatitan (Santa Catarina/Tuapurie), November 1667 © Parroquial Records 1590-1979, Mezquitic, Jalisco, Mexico.

The confessional books used on these visits provide a window into the intimate life of Indigenous peoples, or how these were seen by missionaries. Their repeated visits and interrogations are also indicative of Indigenous resistance to the evangelising process.

Confessionaries followed the Ten Commandments, beginning with the question: Have you loved God above all things?

Questions about sexuality and marriage come under the sixth commandment: You shall not commit impure acts.

Some of these sins were later incorporated into law, with corporal punishment brought in for infidelity and a judge installed in Wixárika communities to police this.

Sexual and intimate life transformed

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

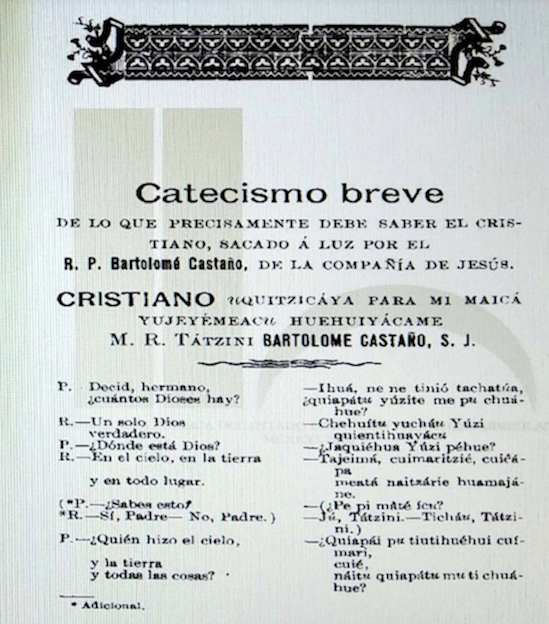

In 1906 Francisco de P. Robles published the only confessional intended specifically for the Wixaritari. Written in Wixárika and Spanish, it preserves the structure of questions according to each of the commandments with specific questions on intimacy:

‘Have you consented to evil desires, with whom, is he/she related, is he/she married?

Was she a maiden, were you already married? Have you spoken indecent things?

Have you committed the sin of sodomy?’

Women were asked if they had fulfilled their duties as a wife and obeyed their husband ‘in all lawful things’.

Colonial laws on marriage

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

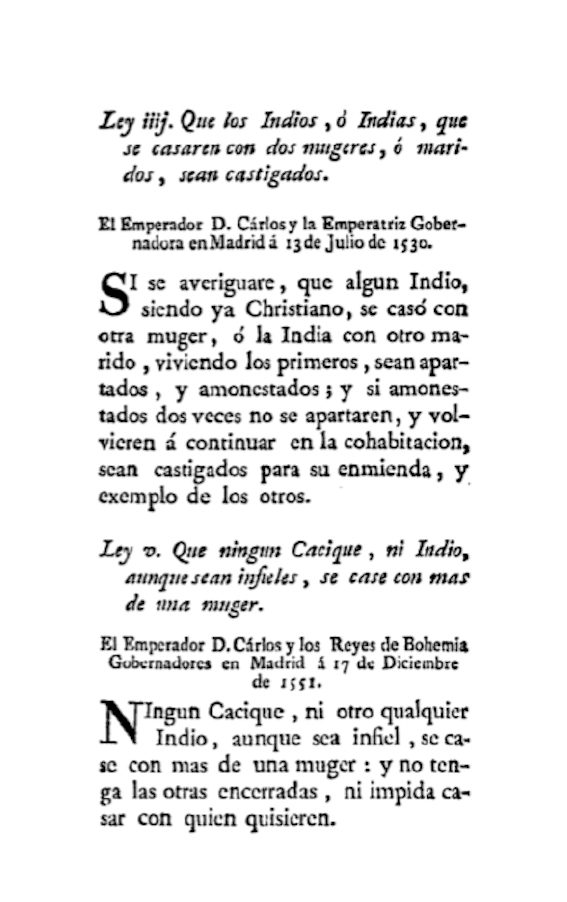

One of the main aims of missionaries was to instil in Indigenous peoples a belief in and adherence to the institution of heterosexual marriage. This was enshrined in colonial law before being enforced in practice during visits to communities.

‘The indians (male or female) that marry two women will be punished’ (1530)

‘No cacique, nor Indian, even if they are unfaithful, can marry another woman’ (1552)

New Colonial Land Relations

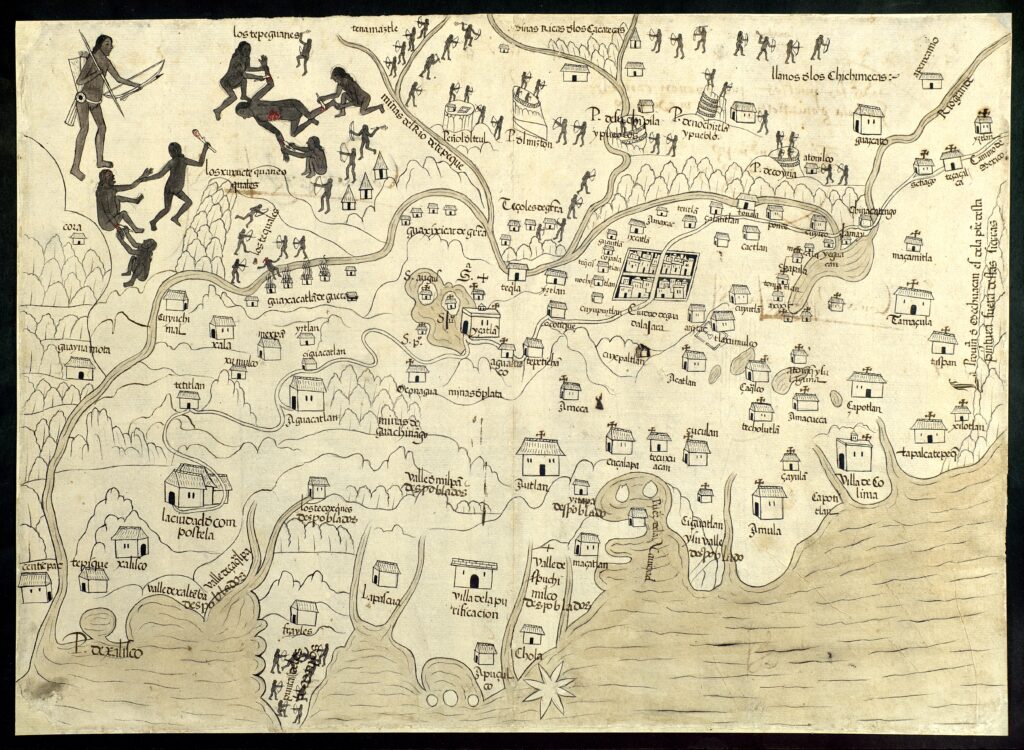

Negotiations man to man: Spanish found complex and diverse societies when they arrived in the Americas.

The semi-nomadic Indigenous peoples to the north and west of Mesoamerica who became known as ‘Chichimecas’ differed socially from the peoples of the centre and south, and were described as ‘barbarians’ and ‘uncivilised’.

Northwest Mexico was colonised after the discovery of silver mines in Zacatecas and was populated with Tlaxcaltec families, allies of the Spanish from central Mexico. The task of the Tlaxcaltecas was to keep the peace on the roads, in particular the silver route, as well as teach good customs and agricultural techniques to groups of insurrectionist ‘indians’ (Guachichiles, Caxcanes, Zacatecos, Huicholes, among others).

From this time on, relations between ‘indians’ and colonisers followed a patriarchal structure: negotiations were man to man. Indigenous groups were governed by men and all negotiations regarding land and natural resources happened between men.

Negotiations over land happened between men:

1733 communication from all-male Wixárika authorities to Captain Antonio de Escobedo requesting the restitution of their territory is a rare example of Wixárika authorities dealing with such negotiations.

Mr. Captain Don Antonio de Escobedo, we come before you in the best form and right that the law confers, to say of this town of Santa Catalina de Quescomatitan [Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán] nation of guisolis [Huichol] governor, Don Marcos Sebastián, Mayor Barela Bernardo and the other Principal Elders Don Luis Sebastian and Don Lorenzo Nicolas, Don Antonio de la Cruz, Don Juan Bautista and Don Juan de la Cruz old current and authorities of the said town and we say as we request for the post of Jonacatique, two sites of cattle with their cavalries that is in a middle of the town of Temsonpa and Noxtic, Hasqueltan and San Sebastian, that our town will be eight leagues this way, which we have known since ancient times...

BPEJ, ARA, C-308-29-4490

View text of image