- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

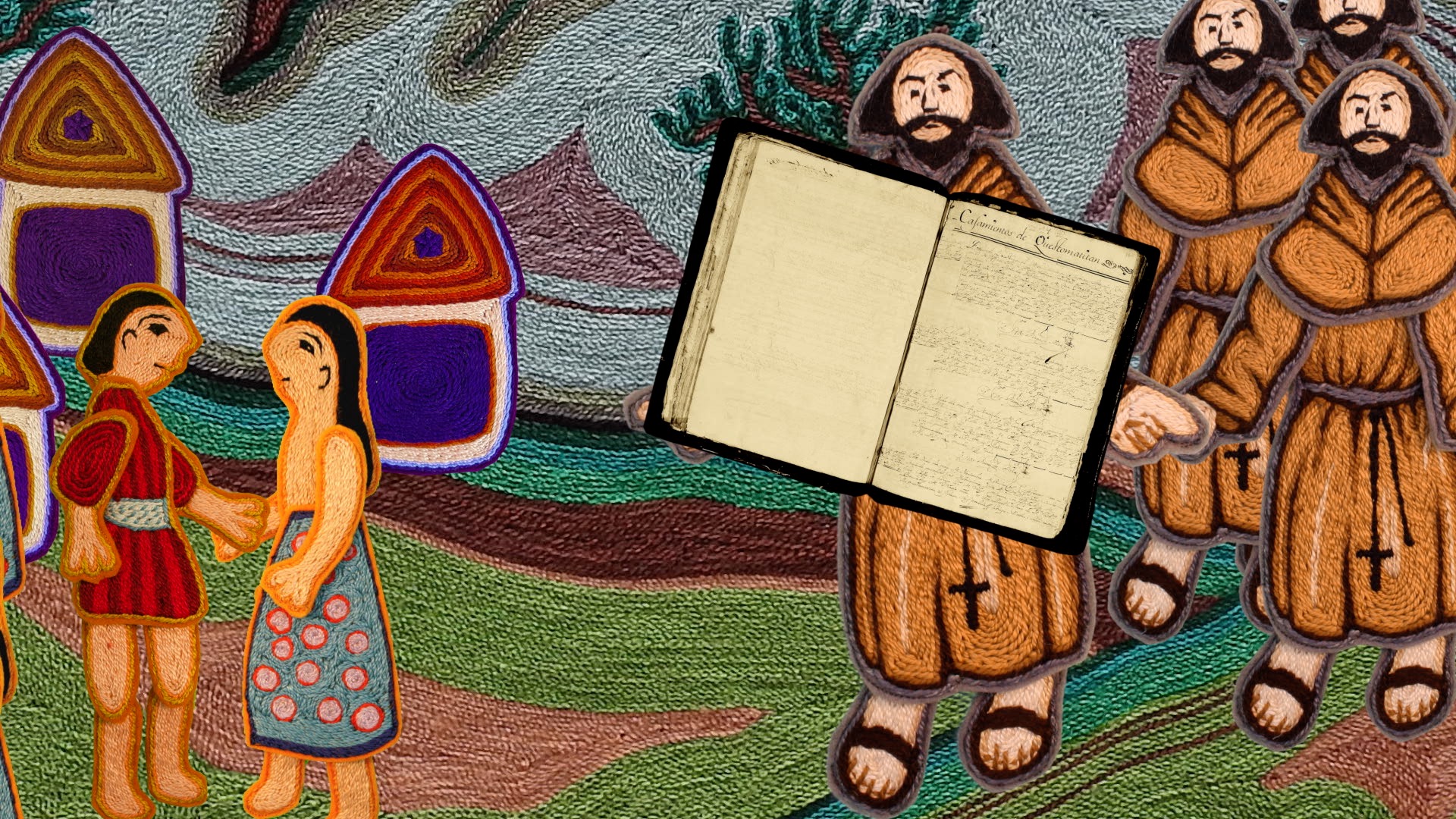

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

What is the Coloniality of Gender?

The coloniality of gender describes how relationships between women, between men and between women and men, changed through the unequal social interactions that began with colonialism and continue to this day.

This colonial “contact zone” is a space where people who have historically been separated, come in to contact with one another and establish ongoing relations, usually in conditions of racial inequality, violence or coercion (Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 1992).

The white European and Christian Man became the standard by which all of humanity was ranked and his position was reinforced by controlling nations and communities of people that were colonised. Like the Wixaritari, many of the nations that were colonised had a more equal gender structure before colonialism: some had women leaders and parallel or complementarity gender systems, meaning that although women and men held different roles, these were equal in status.

The colonial gendering of native people also shaped dominant structures of gender, and the identities, roles, appearance and social organisation of white women and white men changed when they assumed racial superiority over people of colour. By the 19th Century the ‘housewife/breadwinner’ model of European patriarchy was firmly established as the natural order of society and laws and institutions were used to enforce this structure. The role model of the Victorian wife as delicate, weak and sexually reserved, contrasted sharply with images of promiscuous and barely dressed women in the colonies.

Coloniality is an enduring process that did not end when states became independent. Today globalised ideas of masculinity and femininity that are based on Western stereotypes and reproduced by commercial interests have replaced colonial structures of domination.

How did Colonialism and State-making influence Gender and Sexuality?

This process happened directly through encounters such as the visits or residency of missionaries in Indigenous lands and the imposition of a Western education system.

It happened legally and politically through the introduction of laws regarding marriage, land ownership, inheritance or sexuality.

And socially through the acculturation that occurs during sustained contact with government services, in times of conflict or migration and more recently through television, social media and consumerism.

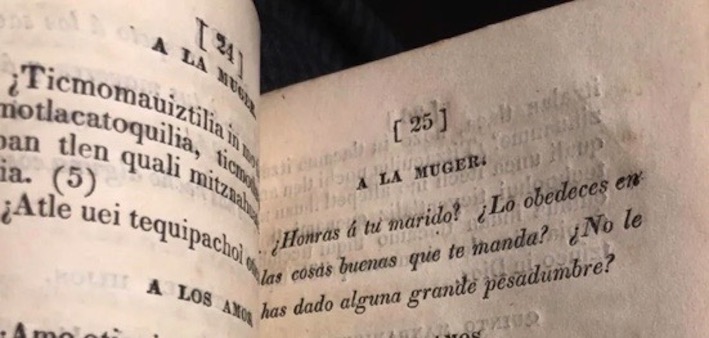

Confessionary Compendium

In Mexican and Castillian,

So that those who do not know the first, can, at least in the case of necessity, administer to the Indigenous [peoples] the Sacrament of Penance.

By a priest of the bishopdom of Puebla

Ancient Printhouse in the Portal de las Flores, 1840.

View text of image

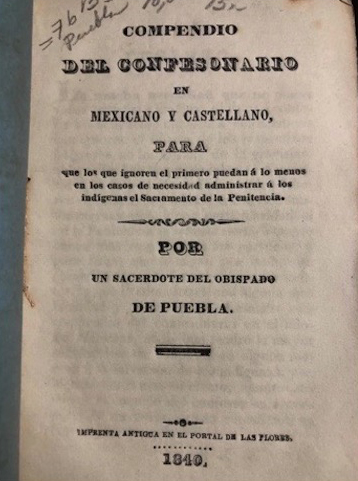

In Mexico this process can roughly be divided into three historical periods:

Click on each 'Contact Zone' above to find out more

The Male Gaze:

Men Writing Men’s Stories

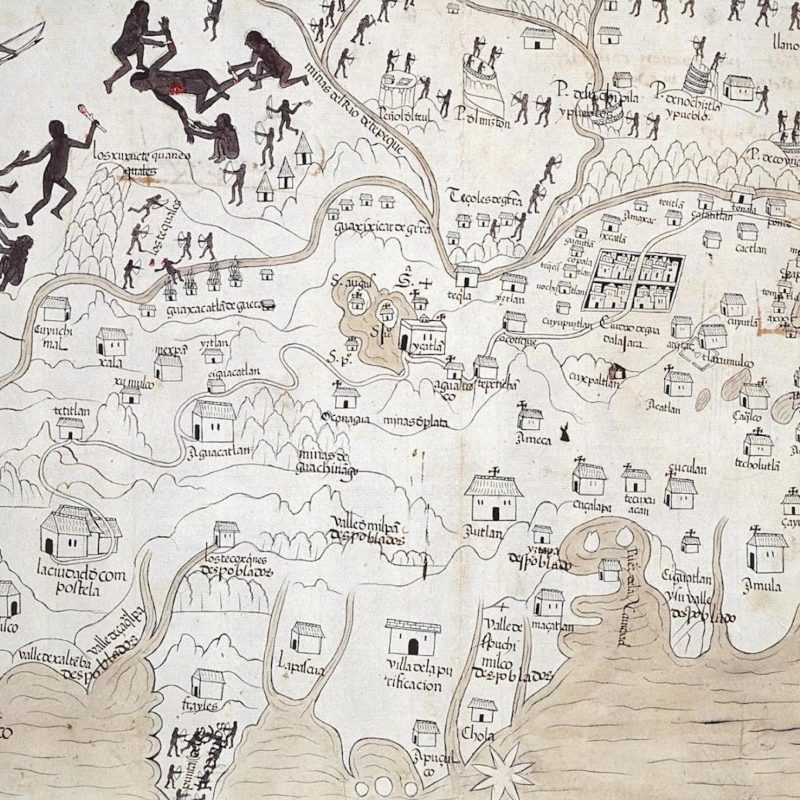

Archive data can only tell a limited story as most archives are collections of documents gathered by the state or powerful institutions and told by men.

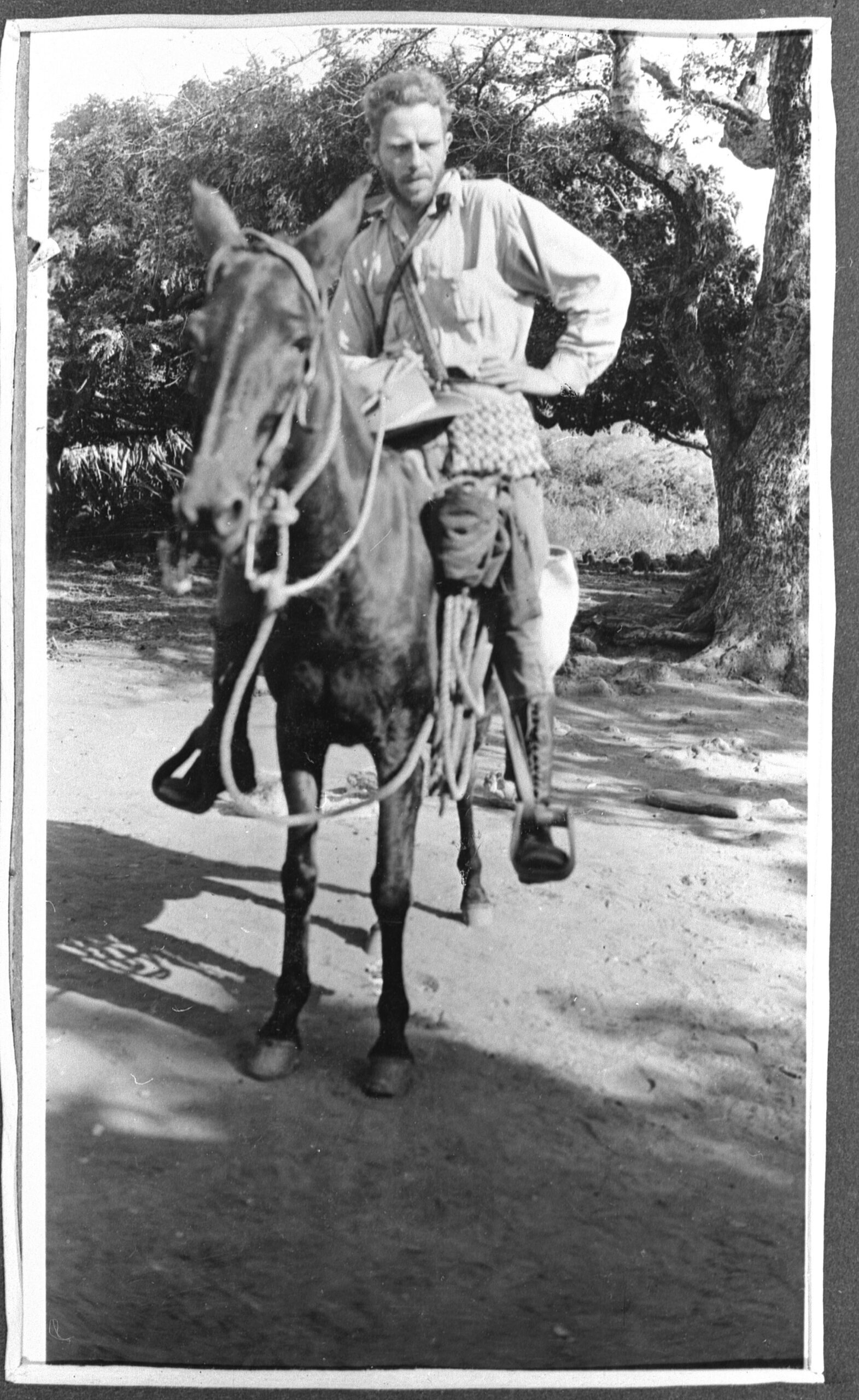

The history of Mexican colonialism and state-making until at least the 1960s, is dominated by men writing stories about and for other men. This white Christian male gaze was defined by beliefs in cultural, racial and sex-based supremacy.

The presence of male anthropologists also taught Indigenous people their subjugated place in the racial and gendered hierarchy. These were some of the conditions and power relationships that shaped early accounts of Indigenous gender relations.

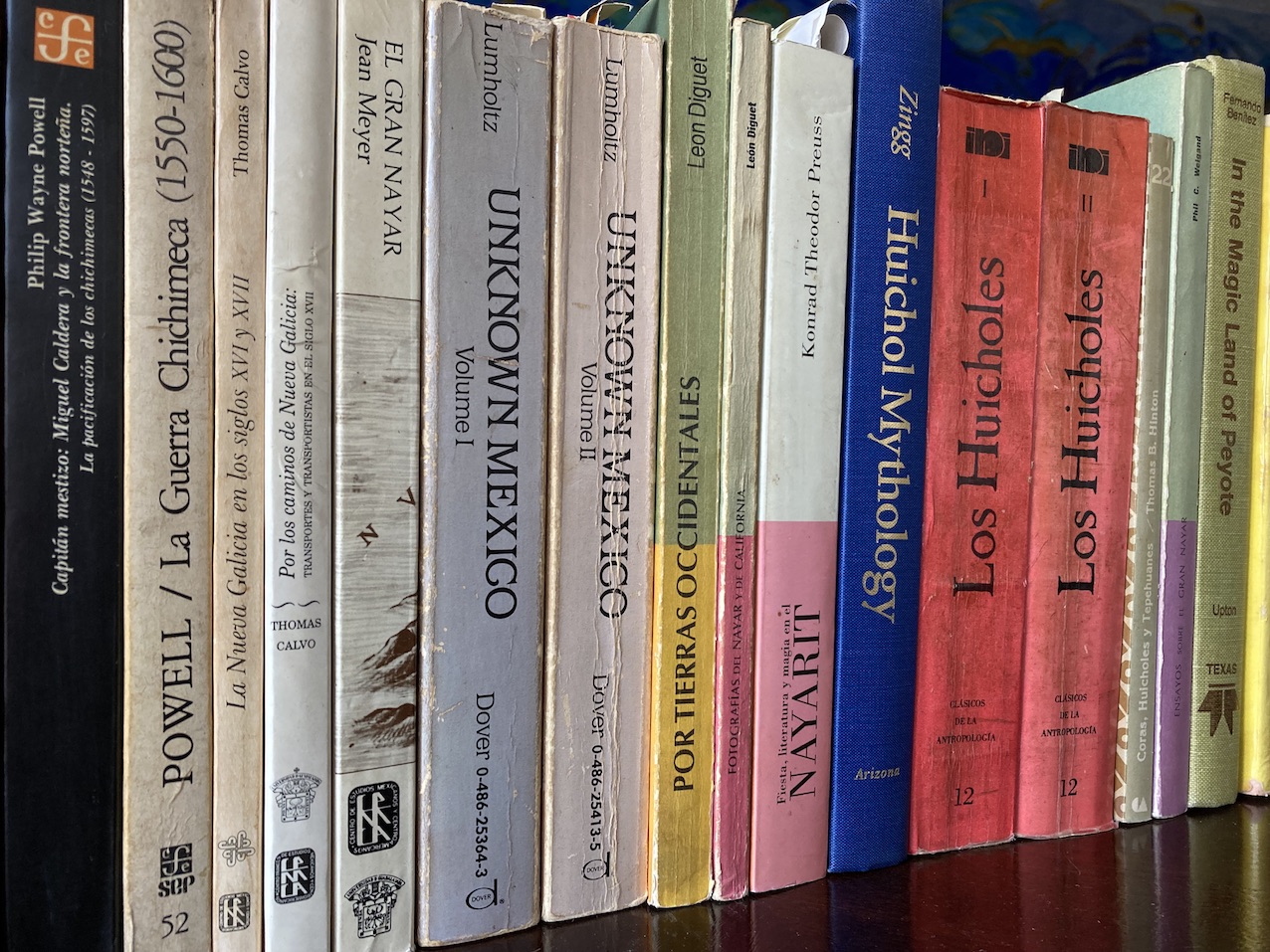

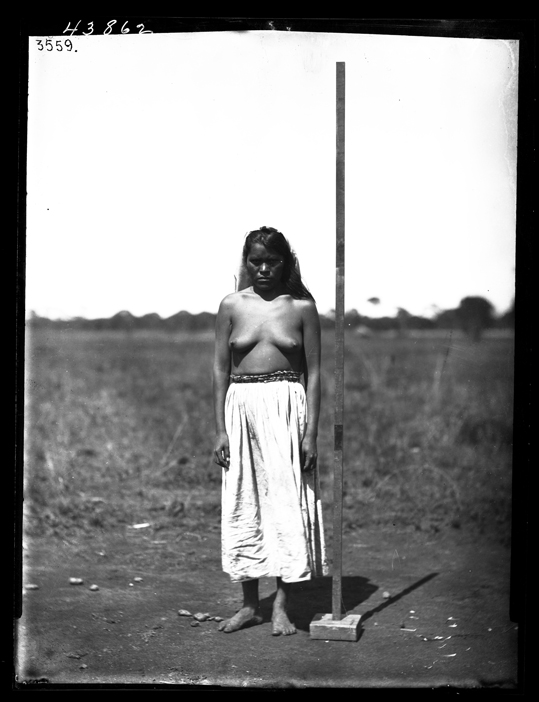

Measuring a Huichol woman, probably San Andrés, Jalisco, 1895 Carl Lumholtz Photography Collection, CL2348 © American Museum of Natural History Library

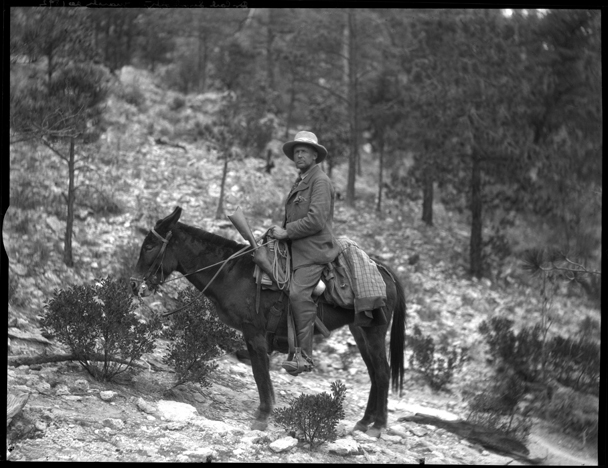

Influential Norwegian anthropologist Carl Lumholtz (1851-1922) author of Unknown Mexico who visited Wixárika communities in the 1890s, wrote at a time when in Mexico as in much of the modern and culturally European world, women had few rights, were considered the property of male members of their family, and Christian, European patriarchy was the natural order of human society.

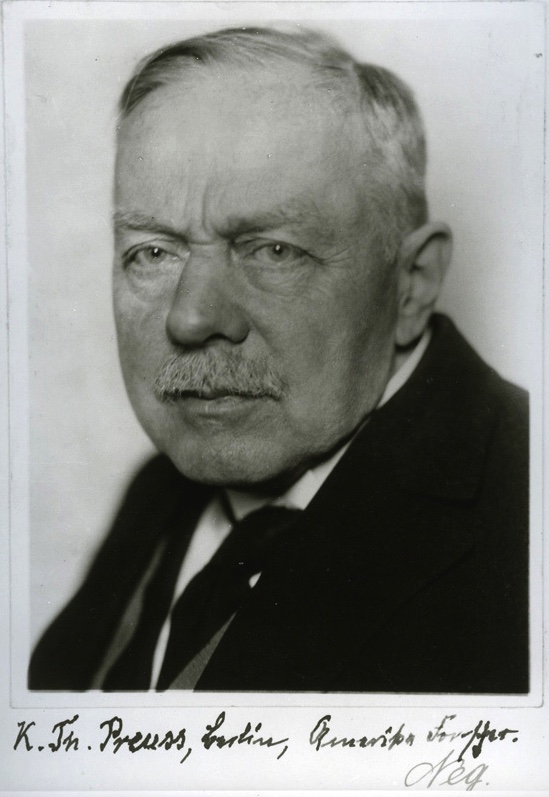

Anthropologists were often also on data and artefact extraction missions. Konrad Preuss 1896-1938, writing in 1907 found a ‘Man of Knowledge’ from whom to learn about Wixárika culture and customs. His informant, José María Carrillo ‘sold [him] the souls [small stones] of his parents and grandparents’.

Konrad Preuss on the Huichols in Stacy Schaefer and Peter Furst, The People of the Peyote, 1996, University of New Mexico Press

As a naturalist, Diguet sought to document human life in line with biological and evolutionary sciences, offering the partial and patriarchal perspective that dominated ethnographic research during that period.

'Huichol Indian' Print by León Diguet, 19th Century ©Musee du Quai Branly

SENSITIVE CONTENT WARNING

This photo is being used to show how anthropological research was used as evidence for theories of scientific racism.

The colonial male gaze of Zingg is evident in his contrasting descriptions of Huichol and Tarahumara women, he writes:

‘In contrast to the ugly, churlish Tarahumara women, who nag their husbands constantly to maintain a status equal to that of the men, the prettier and much more affectionate and amiable Huichol women are poorly treated.’

The Huichols, Primitive Artists, Robert Zingg (1938), p.142