- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

Contact Zone II

Patriarchy and Ethnocide

in the New Republic

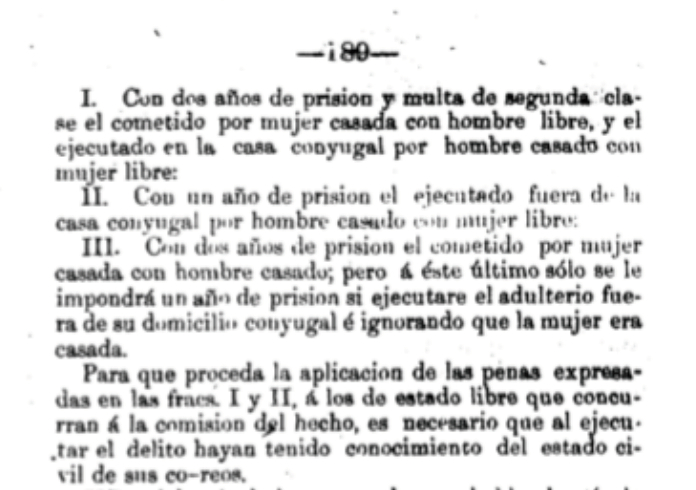

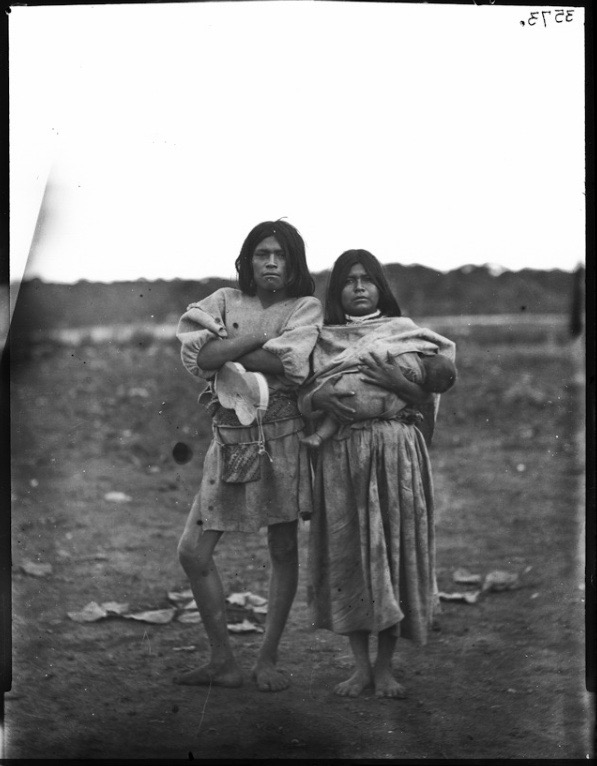

Huichol couples, San José, Jalisco, 1895. Carl Lumholtz Photography Collection, CL2222 © American Museum of Natural History Library

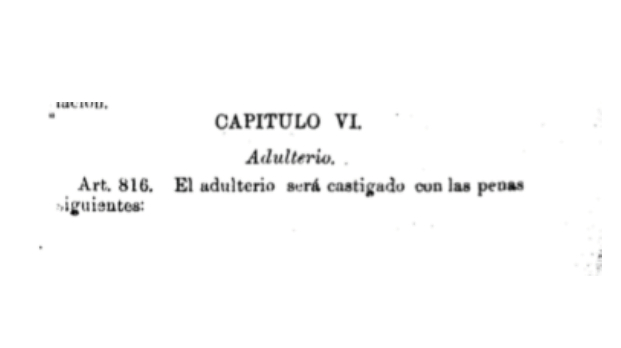

Mexico gained independence in 1821 and over the following decades the Liberal state began to legislate on moral codes of conduct in ways that gave men power and control over women. As an example, adultery was punishable with one or two years in prison but harsher sentences were given to women than men.

Huichol couples, San José, Jalisco, 1895. Carl Lumholtz Photography Collection, CL2222 © American Museum of Natural History Library

At the same time agrarian policy saw the privatisation of land and the introduction of patriarchal inheritance laws. These legal transformations contributed to the masculinisation of public spaces and feminisation of private and domestic spheres, reflecting modern and European lifestyles.

This gendering of spaces was hierarchical with men’s public roles endowed with a higher status than domestic roles that were attributed to women. In contrast, as the growing of maize and female fertility were both highly venerated, it is likely that in pre-colonial societies the tasks of food preparation and child rearing were parallel in status to the public and political roles of men.

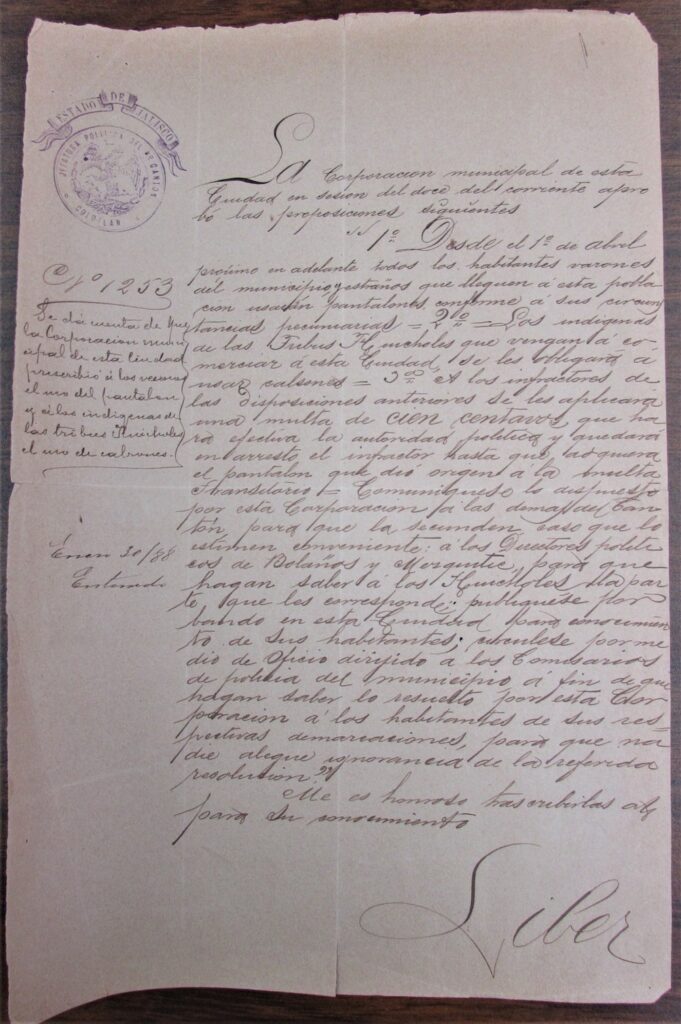

Excerpt of Mexican State law

Chapter VI Adultery.

Article 816, Adultery will be punished with the following penalties:

1. With two years in prison and a second-class fine that which is committed by a married woman and a free man, and that which is committed in the conjugal home by a married man and free woman.

2. With one year in prison that which is committed outside the conjugal home by a married man and free woman.

3. With two years in prison that committed by a married woman and a married man, but this last will only be one year in prison if the adultery is committed outside the conjugal home and he did not know that the woman was married.

View text of images

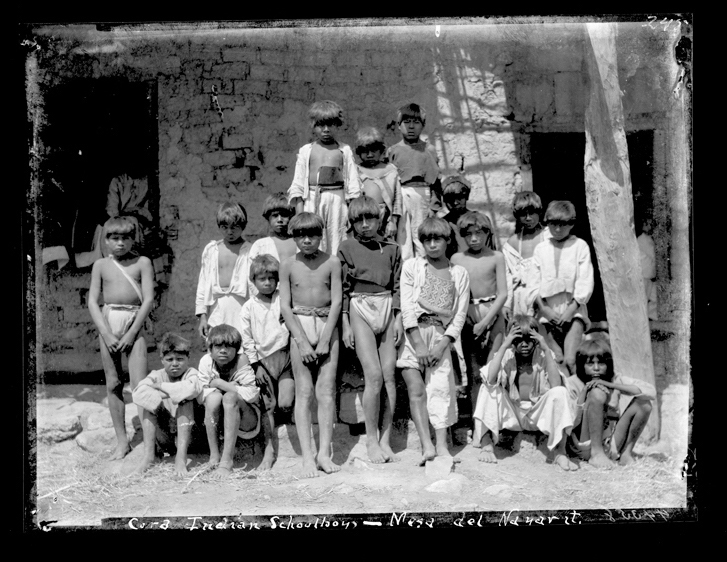

In continuity with colonial efforts to scientifically differentiate and rank human races, travellers to Indigenous regions of Mexico photographed, measured and weighed women and men. Civilising missions to Wixárika communities continued and towards the end of the 19th Century the first schools were established, although very few girls attended. In alignment with national legislation, girls were taught by women and boys by men, with curriculums reflecting the different gender expectations of the time.

The Patriarchal Family

Chronology of Travellers’ Chronicles

Through images and ethnographies of 19th and early 20th Century we see the male gaze of the era describing the clothing, bodies and customs of people considered savage and uncivilised.

Clothing

Female Authority

Use of bow and arrow

Salt trade

Use of bow and arrow

Marriage

Clothing

Childbirth

Intimate partnerships

Female role in household

Courtship

Local Authorities

Huichol Authorities (functions)

Settlements

Gendered organisation of work

Childbirth

Christening (by gender)

Marriage

Sexuality

Religion

Fiestas

Illnesses

Relationships with parishioners

Education

Intimate partnerships

Mothers and newborns

Men’s responsibilities

Masculine and Feminine in Mythology

Wixárika women and gender in the late 19th Century

‘As a rule, hearts are easily won, and easily lost . A husband, in his rage, may even beat his wife, or she, on discovering that her spouse has been led astray, may be so offended as to leave him. On the whole the women are more faithful than the men. The sexes as dependent on each other in more ways than one; for one provides, the other prepares the food.’

Carl Lumholtz in Unknown Mexico

Wixárika women and gender in the late 19th Century

‘As a rule, hearts are easily won, and easily lost . A husband, in his rage, may even beat his wife, or she, on discovering that her spouse has been led astray, may be so offended as to leave him. On the whole the women are more faithful than the men. The sexes as dependent on each other in more ways than one; for one provides, the other prepares the food.’

Carl Lumholtz in Unknown Mexico

'Nowhere as much as here, do hunger and love keep the world a-going …the fair sex is much more appreciated; and this being so, the women as a rule are able to decide their own fates. Their position in the family is high'

Unknown Mexico, Carl Lumholtz

‘The Huichols, in general they use as a dress a cloth called 'jolote' with an opening for the head; it reaches about half way down their thigh and they tie it with a wide belt. From this band they tie a multitude of sacks of different size, all woven. On their backs, tied at the front, they carry a large basket lined with deer skin and filled with arrows; on their arm a bow of brazil and on their head a hat with a small, narrow cup that they tie with a ribbon’

Rosendo Corona (1899) in Santoscoy

'Indigenous people from the Huichol tribe that come to this city must wear trousers'

JALISCO STATE

Following the trend for enshrining moral ideas in law, in 1888 the city of Colotlán, in the foothills of the Wixárika highlands, decreed that all male visitors to the city were required to wear trousers. Huichols were specifically required to wear calzones (pants/breeches) as seen in the 1895 gallery image of a couple and child on horseback.

1º Desde el primero de abril próximo en adelante todos los habitantes varones del municipio y extraños que lleguen a esta población usarán pantalones conforme a sus circunstancias pecuniarias. 2º Los indígenas de las tribus huicholes que vengan a comerciar a esta ciudad se les obligará a usar calzones. 3ª A los infractores de las disposiciones anteriores se les aplicará una multa de cien centavos, que hará efectiva la autoridad política y quedará en arresto el infractor hasta que adquiera el pantalón que dio origen a la multa.

© Archivo Histórico del estado de Jalisco, G-9-888 C34-E4

‘They wear their hair long, tied at the front with a ribbon in a single plait. On their neck some wear wide strings of beads and some wear earrings of the same. On their feet they wear strongly tied sandals. In the winter they wear blankets, almost always white with blue or black ties. The women don’t wear sandals or a hat, nor bow nor bags; they wear a short petticoat of coarse cloth (manta) that reaches below the knee, and the jolote; most wear bead earrings and bracelets; the last of these they use on their ankles.’

Rosendo Corona in Santoscoy, 1899

19th Century Politics of Ethnocide

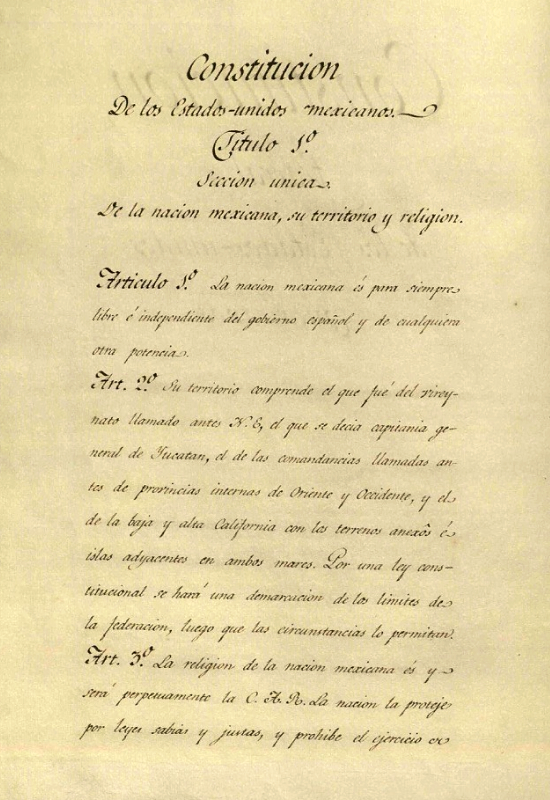

The Mexican nation is sovereign and free from the Spanish Government (1824 Constitution)

Throughout the 19th Century the Mexican state attempted to create a new mestizo and Spanish speaking citizen. It was hoped that secular education and the extensive use of Spanish would eliminate racial and cultural differences.

While the Spanish Crown had recognised the need to grant Indigenous people property rights and access to justice as a means of retaining control over local power structures, the newly independent state had a different set of objectives. Agriculture, the economic motor of the country, required small landowners and productive citizens. Indigenous communities should divide their land and produce individually as private owners.

With the new constitution of 1824 Indigenous people lost their colonial status as ‘indians’, and the accompanying set of protections, including access to the General Indian Court, that had been established in 1592. After independence there was no legal differentiation between Indigenous and European people, making them more vulnerable to land and labour exploitation by the political and economic elites.

Elizabeth Dore describes how this happened:

‘With the rise of private property in land, parents’ legal obligation upon their death to divide property equally among their legitimate children, or mandatory partible inheritance, was abolished in Mexico… With new laws promoting privatization of land, which transformed property relations in all social strata, including the peasantry, the elimination of the guarantee that women receive an equal portion of their parents’ estate, no matter how grand or humble it might be, worked to undermine women’s economic security’

Elizabeth Dore, ‘One step forward, two steps back. Gender and the state in the long 19th Century’ in Elizabeth Dore and Maxine Molyneux Hidden Histories of Gender and the State in Latin America, 2000

We are citizens. Land privatisation and invasion.

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

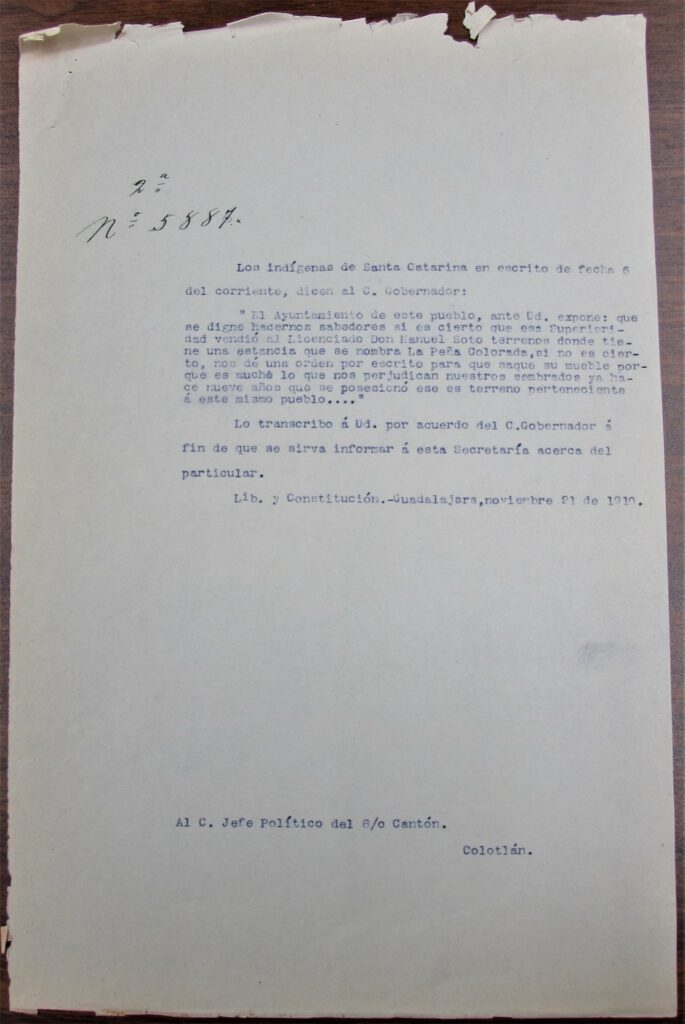

Inequality grew in the United States of Mexico during the 19th Century and land invasions were frequent but these were not received passively in Wixárika territory, and the fight for their lands remained a consistent theme.

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

As is noted in this 1910 demand to the City Council of Colotlán, the Indigenous people of Santa Catarina demanded to know whether the Mayor had sold Peña Colorada, a piece of their territory, to a certain Don Manuel Soto, a local landowner. The Indigenous leaders of Wixárika communities were drawn into Mestizo politics to defend their territory in continuity with the man-to-man negotiations that began under colonialism.

Liberal Education

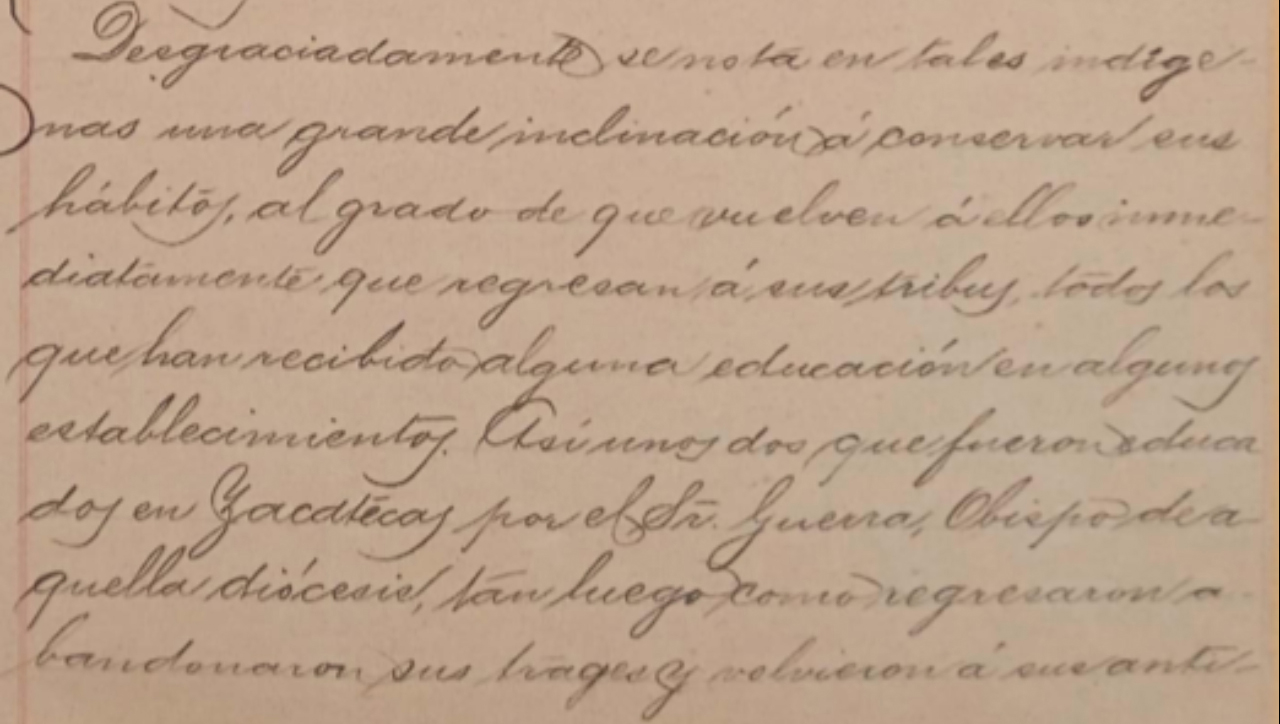

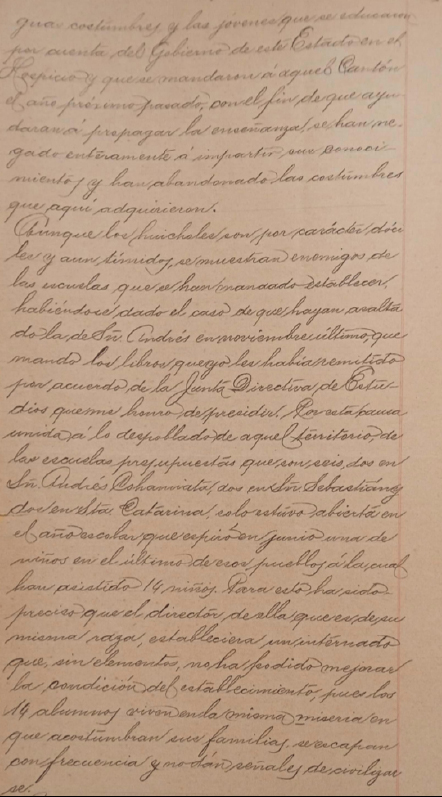

Teachers’ report excerpt © Biblioteca Pública del Estado de Jalisco “Juan José Arreola”, Instrucción Pública, 79-46-2367.

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

The first schools were established in Wixárika territory in the late 19th Century, although Mestizo teachers describe very little willingness to study and ‘no signs of civilising’. The racialising language used in these early educators’ reports are indicative of the caste system established by colonialism but also of the resistance by Wixaritari to modern forms of social organisation that the education systems intended to bring.

Teachers’ report excerpt © Biblioteca Pública del Estado de Jalisco “Juan José Arreola”, Instrucción Pública, 79-46-2367

Liberal Education

Teachers’ report excerpt © Biblioteca Pública del Estado de Jalisco “Juan José Arreola”, Instrucción Pública, 79-46-2367.

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

The first schools were established in Wixárika territory in the late 19th Century, although Mestizo teachers describe very little willingness to study and ‘no signs of civilising’. The racialising language used in these early educators’ reports are indicative of the caste system established by colonialism but also of the resistance by Wixaritari to modern forms of social organisation that the education systems intended to bring.