- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

- How The Intimate Lives Of Wixárika People Were Changed Forever

- Who are the Wixaritari or Huichol

- What is the Coloniality of Gender

- Contact Zone I: The Evangelisation of Intimate Life

- Contact Zone II: Patriarchy and ethnocide in the new Republic

- Contact Zone III: Nation, revolution and the modernisation of patriarchy

- Wixárika Women and Gender in the Indigenous 21st

Contact Zone III

Nation, Revolution and the

Modernisation of Patriarchy

After the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), the state reinforced a gender order based on the nuclear family.

Revolutionary legislation defined men as heads of households with women and children as their dependents. Only widows could acquire land by inheritance, but women did participate in the political economy and social life of ejidos. As mothers and moralisers of the community women were expected to form anti-alcohol leagues and to support education. To raise healthy children, mothers had to have maternity services and be involved in childcare issues. These policies promoted the domesticity of women, in contrast to male citizenship: military service, wage work and civic engagement.

Gender policies were put in place that sought the modernization of patriarchy.

Women remained second-class citizens, subject to male domination, but with roles in the domestic and social spheres that would assist the state as mothers in the modernising process, in education, health, morality, and child protection.

In the ejidos, men, women and young people should have access to schools and medical services. Although state-level policies such as these did not reach Wixárika communities, their establishment as hegemonic forms of social organisation had reverberations in all their interactions with state institutions and education systems.

New Ways to Inhabit the Nation

Revolution and Agrarian Reform

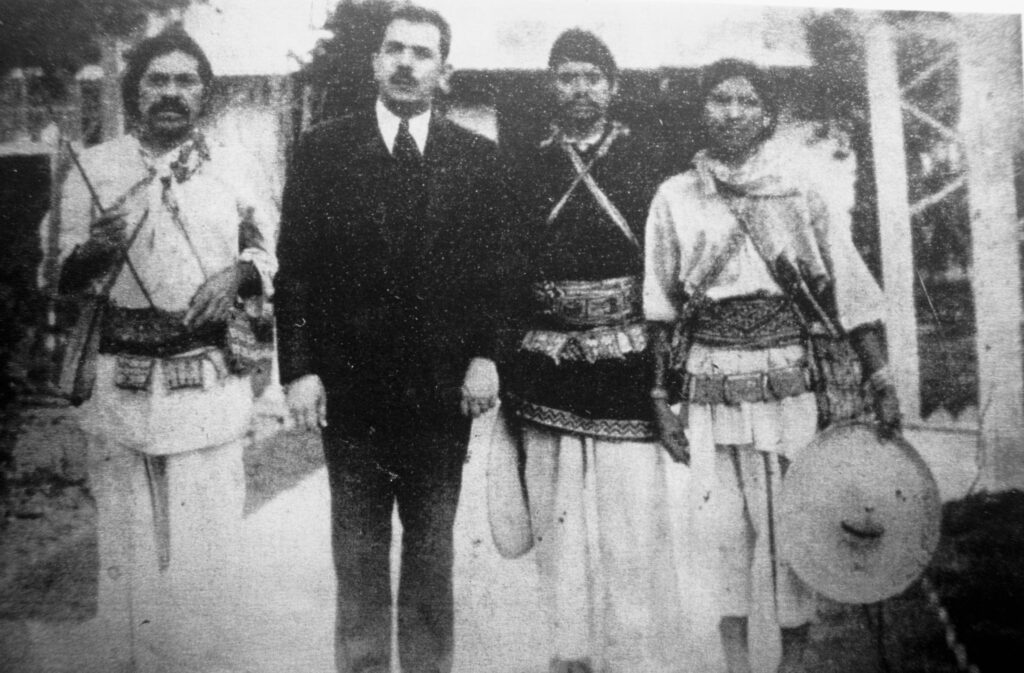

The violence of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) and the Cristero war (1926-1929; 1930s) forced many families to leave their traditional territories, changing their everyday lives and rituals.

The withdrawal of missionaries and the institutionalisation of ‘modern’ political systems in Indigenous communities during the post revolutionary years was also accompanied by more frequent land invasions. Attacks by armed Cristero soldiers who burned homes, raped women and stole cattle are still within living memory.

The 'Cristeros' were leaving the ranches with nothing, literally. People said that when they arrived in Pochotita, after they did their misdeeds, they set fire to the ‘tuki’ and unloaded the ‘metates’ (grass matts) they had stolen, and they said to the women: “Prepare the nixtamal and make tortillas”. While my grandmother was cooking she saw how they sacrificed the stallion bull of my great-grandfather Kwainurie. It was the largest bull in the herd, it was called Tseɨyema. They loved the bull very much and my grandmother used to say that out of sheer sadness and anger she did not eat for five days.

Lucía Candelario

In the 1970s the first bilingual school opened in Tuapurie in the newly founded town of Nueva Colonia which was to become a centre for state led development interventions including a clinic, primary school with boarding facilities and in 1996 a Telesecundaria.

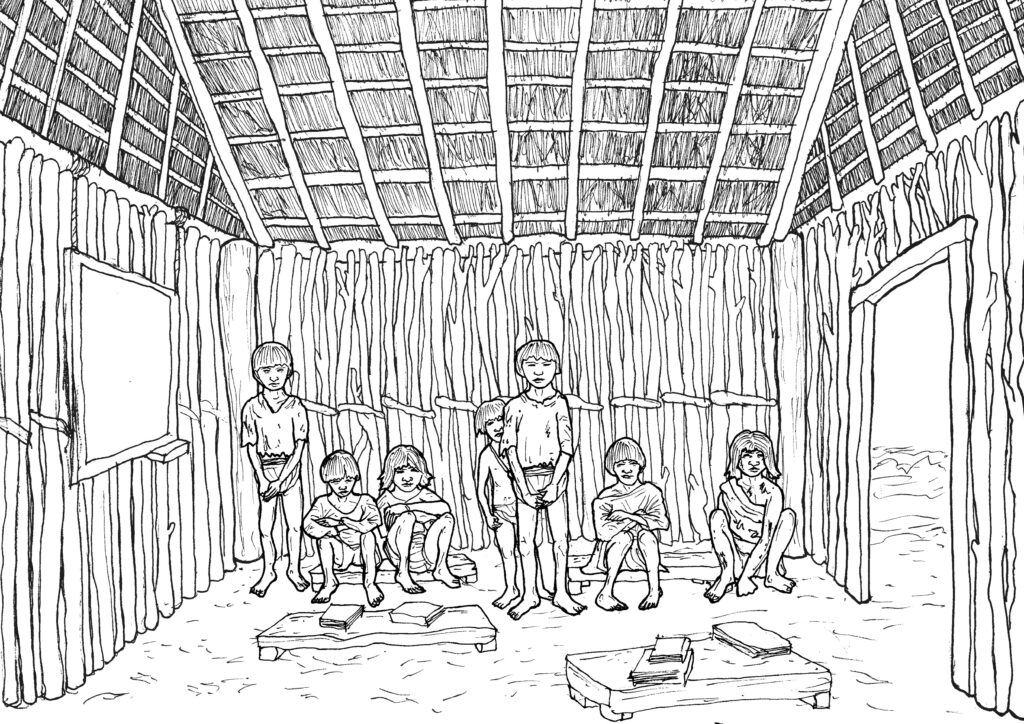

“we go to Sandoval's school made out of oak branches. It is very spacious inside and has school benches, a blackboard, chalks and school books. The pupils, about 6 in number, are something else. One has no pants and all are fairly ragged and dirty, but well behaved and quiet.”

(Collette Lily, Field Diary (inedit) 1971)

The arrival of Modernisation and the National Indigenous Institute

The coloniality of state-Indigenous relationships once again changed with the establishment of the National Indigenous Institute (INI by its Spanish acronym) in 1948. The INI promoted an integrationist stance of assimilating Indigenous communities into mestizo economic, social and political life through protection and acculturation.

Their policy which ‘propose[d] to furnish indigenous communities with cultural elements of positive value, in the government’s view, as replacements for cultural elements which are valued negatively in the indigenous communities themselves’ (Alfonso Caso 1958, Human Organisation) reflected the gender order of the time.

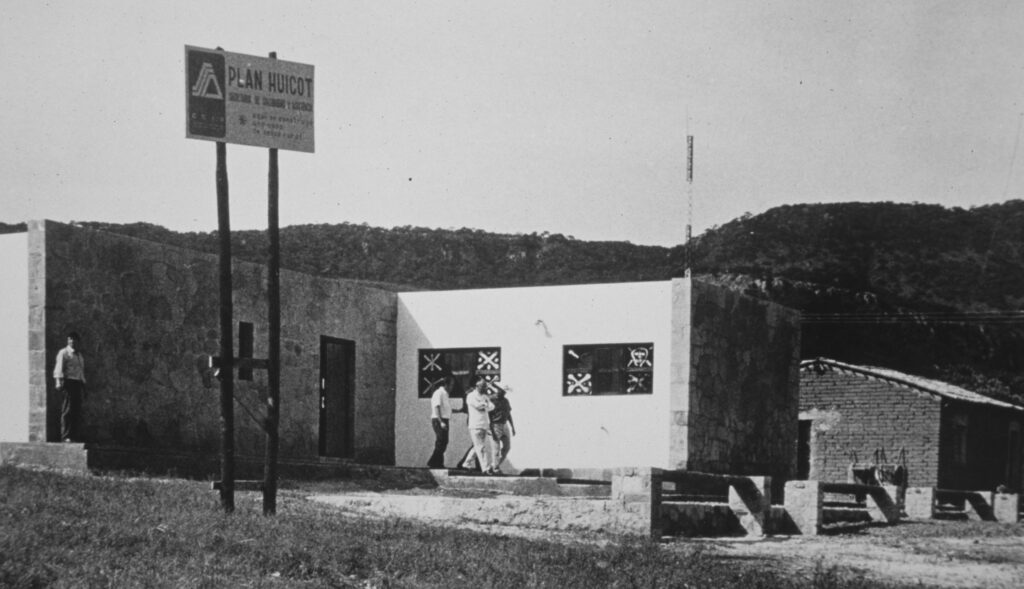

After the political upheavals of 1968 a group of progressive anthropologists led by Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, whose definition of Indigenous peoples was as survivors who had managed to resist acculturation despite centuries of oppression, took over the INI’s leadership. Bonfil Batalla led the INI when the Plan Huicot was developed to serve Huichol, Cora and Tepehuano communities of the the Gran Nayar region. Soon 60 Indigenous Coordinating Centres were established across Mexico with the coordinator of each centre speaking for the state. This new indigenismo promoted self-management: whereas in the past Indigenous school teachers had returned to their communities to encourage integration, now their role was to support cultural difference though bilingual education.

In the 1970s the first bilingual school opened in Tuapurie in the newly founded town of Nueva Colonia which was to become a centre for state led development interventions including a clinic, primary school with boarding facilities and in 1996 a Telesecundaria.

“we go to Sandoval's school made out of oak branches. It is very spacious inside and has school benches, a blackboard, chalks and school books. The pupils, about 6 in number, are something else. One has no pants and all are fairly ragged and dirty, but well behaved and quiet.”

(Collette Lily, Field Diary (inedit) 1971)

The arrival of Modernisation and the National Indigenous Institute

The coloniality of state-Indigenous relationships once again changed with the establishment of the National Indigenous Institute (INI by its Spanish acronym) in 1948. The INI promoted an integrationist stance of assimilating Indigenous communities into mestizo economic, social and political life through protection and acculturation.

Their policy which ‘propose[d] to furnish indigenous communities with cultural elements of positive value, in the government’s view, as replacements for cultural elements which are valued negatively in the indigenous communities themselves’ (Alfonso Caso 1958, Human Organisation) reflected the gender order of the time.

After the political upheavals of 1968 a group of progressive anthropologists led by Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, whose definition of Indigenous peoples was as survivors who had managed to resist acculturation despite centuries of oppression, took over the INI’s leadership. Bonfil Batalla led the INI when the Plan Huicot was developed to serve Huichol, Cora and Tepehuano communities of the the Gran Nayar region. Soon 60 Indigenous Coordinating Centres were established across Mexico with the coordinator of each centre speaking for the state. This new indigenismo promoted self-management: whereas in the past Indigenous school teachers had returned to their communities to encourage integration, now their role was to support cultural difference though bilingual education.

In 1971 the Coordinating Centre for the Development of the Huicot region (‘Plan Huicot’) was created.

During the six-year term of President Luis Echeverría from 1970 to 1976, the federal government implemented the Plan Huicot which, according to the government report presented to the Congress of the Union in 1971 included ‘the initiation of a network of penetration roads, the construction of airstrips in 22 towns, the establishment of radio communication services, the construction of health centers and houses, 32 tents of the National People’s Subsistence Company, water systems in six villages and other services’.

This indigenismo was developmentalist, at a time when it was inconceivable that progress could mean anything other than modernisation.

Although the plan was well intentioned, it was founded on a poor understanding of Indigenous peoples and their historical relationship with the state, as the plan explains ‘penetrating the conscience of these nucleus’ of population so that they collaborate in the solutions to their own problems is not easy, especially in that which concerns land ownership’.

A specific focus on women or gender was entirely absent from the ‘Plan Huicot’, whose primary focus was on land security and disrupting ‘the barriers of distrust, insecurity and misery’ that Wixaritari, Coras and Tepehuanos faced.

The Wixárika people’s longstanding rejection of state and religious interventions was considered a barrier to development, not a concern to be understood, and development plans focused on creating the infrastructure for economic incorporation.

The plan was also primarily an infrastructure project, building schools with boarding facilities, clinics, roads and airstrips.

Alongside the clinic infrastructure, public health, education and sanitation programmes were proposed with a focus on reducing infectious diseases. The gender specific needs of women such as maternal healthcare provision or sexual and reproductive healthcare services would not come for many decades.

Technology reaches the Wixárika

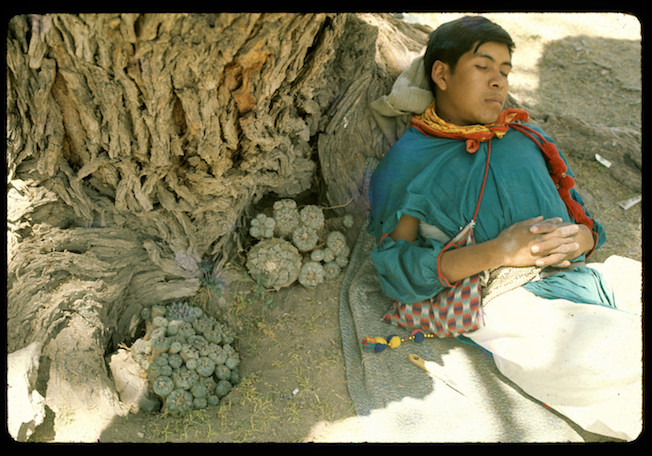

The ‘Plan Huicot’ was being developed when Neil Armstrong landed on the moon. John Lilly had accompanied a group of Wixaritari to Wirikuta to gather peyote cactus when the radio broadcast the first moon landing. John photographed and audio recorded the occasion.

Resting in Huiricuta while hearing on the radio of man landing on the moon. ©Colette Lilly, 1969. Archivo CHAC-Lilly

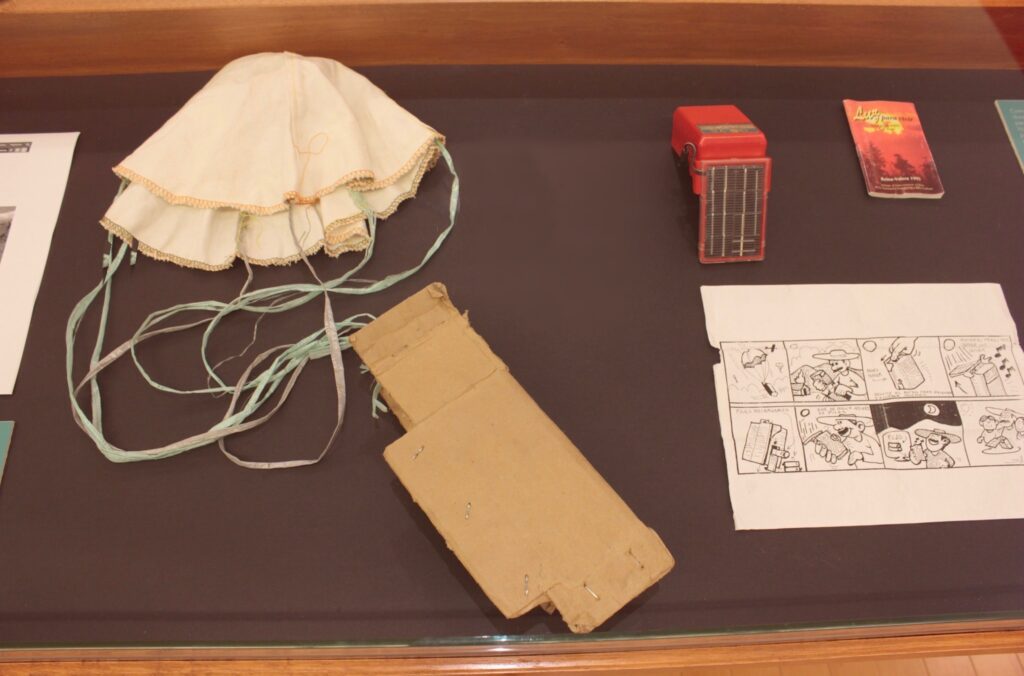

Evangelisation efforts did not disappear in the 20th Century, they simply became more sophisticated and communities responded rapidly.

As part of their infiltration and indoctrination campaigns, during 1999 an evangelical religious group dropped radios with parachutes from small planes flying over the Sierra Huichol.

The community of Tuapurie took the unanimous decision to eliminate this threat, not only because of the ideological invasion it entailed, but also because of the ecological pollution that “the hallelujahs” were doing, as these North American sects are referred to in the Sierra.

The comuneros organised themselves to collect the radios scattered across their territory, stacked them and set them on fire during an assembly. By community agreement, the piece that is exhibited here as evidence and memory was safeguarded.

Gender in early 20th Century Ethnography

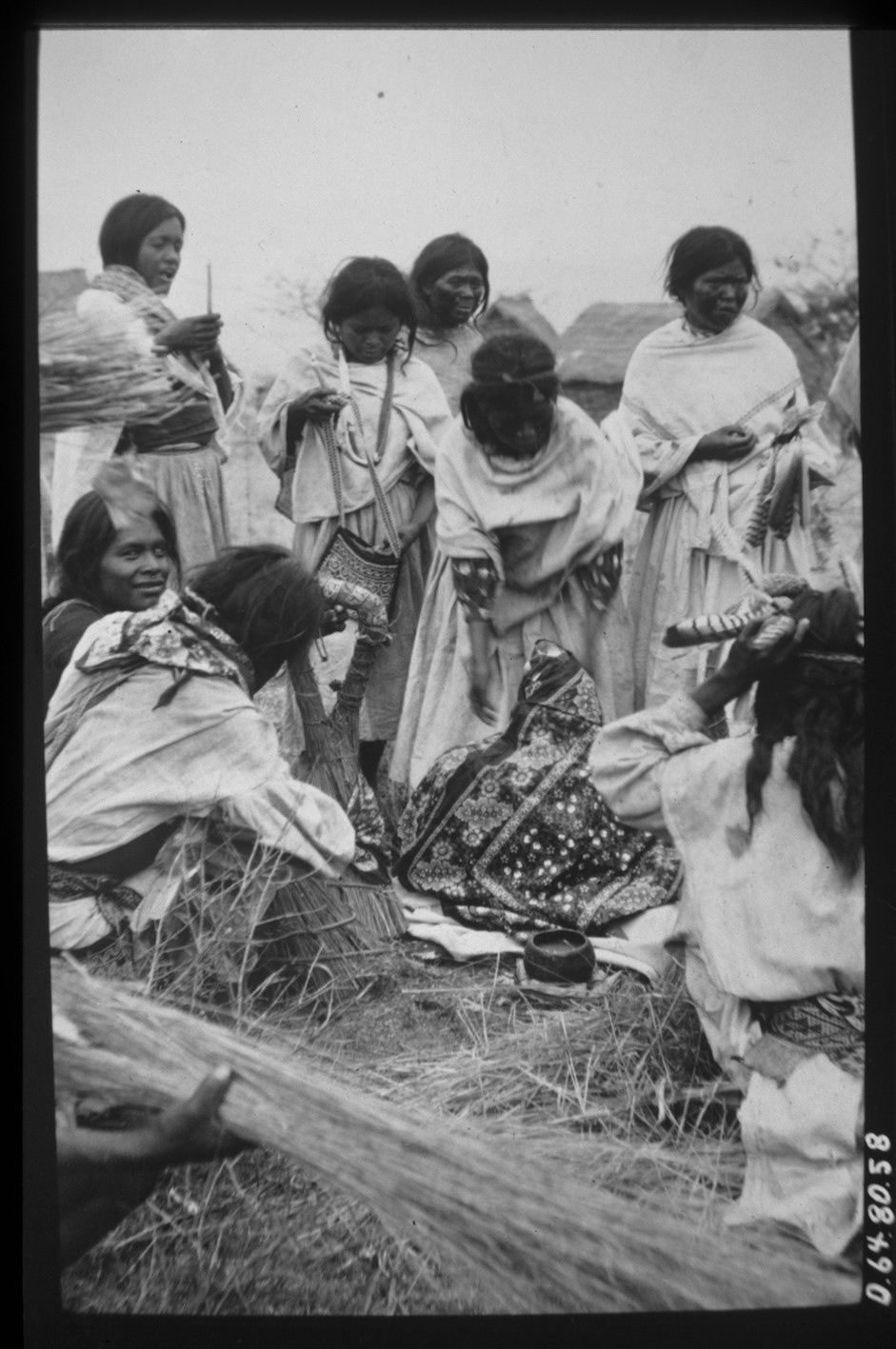

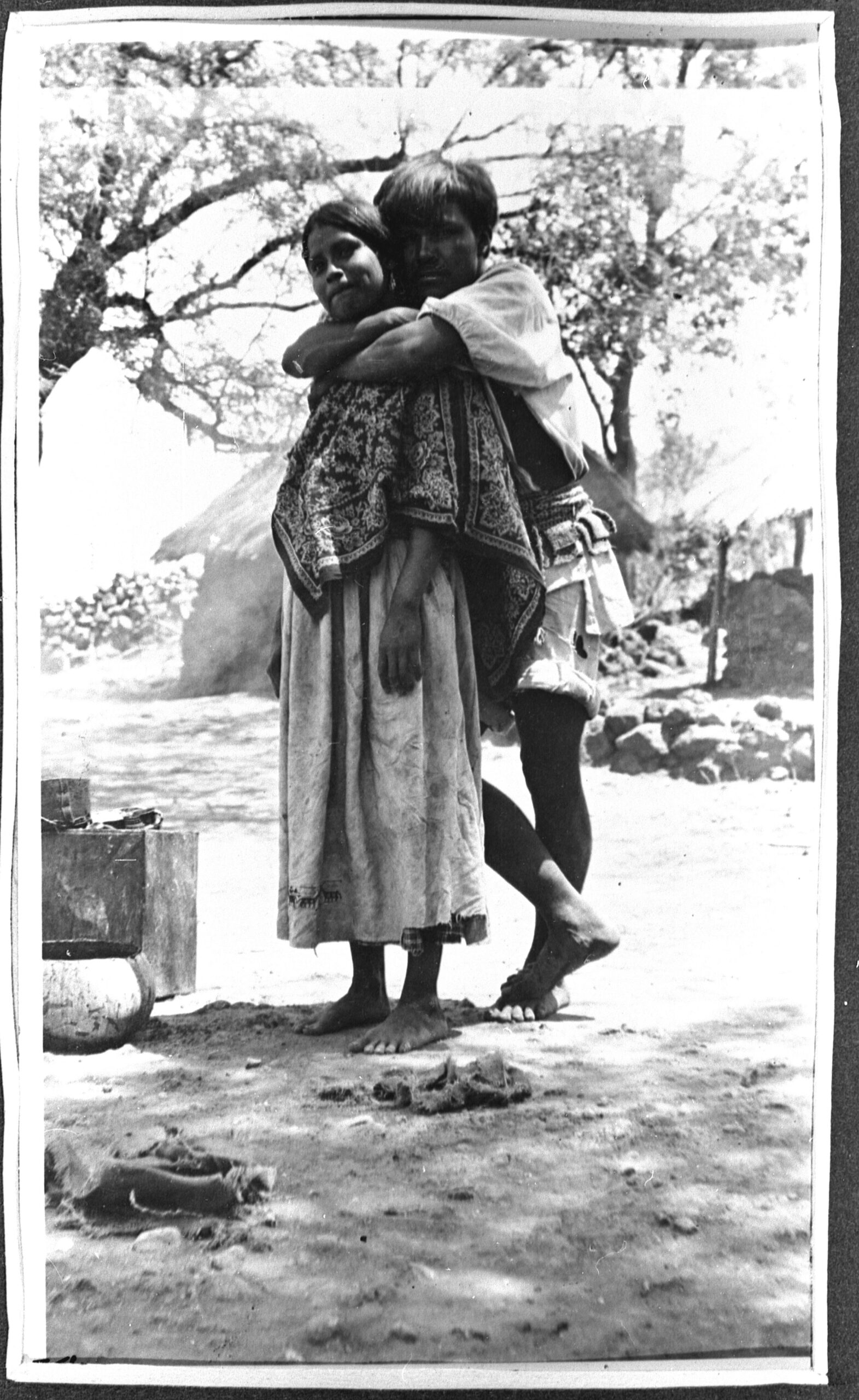

In earlier times, the union between a woman and a man was something of a match made in heaven: a partnership guided and governed by their shared responsibilities toward divine ancestors and ensuring an abundance of rain to grow their scared maize. As Catholic moral codes were gradually assimilated by Wixárika communities, so were a series of kinship patterns, heteronormative ideas about intimate life, social norms and transgressions.

Since the early years of colonialism, how Wixárika women and men arranged their intimate lives has been influenced by many factors including the continued encroachment of Catholicism, local government structures and relations with the colonial state, codes of crime and punishment, national legislation regarding intimate partnerships and school attendance.

The primary task of Franciscan missionaries visiting the Sierra Wixárika was to instil the catholic notion of marriage in people’s minds. We know from confessionary documents, the writings of Franciscan missionaries and travellers that partnerships between men and women had never been very strong. Both were sexually freer and sex between two people of the same gender was not taboo. It is likely that women were held in high regard because of their fertility and this gave them a degree of sacred power over men.

As the centuries progressed, catholic values influenced how women and men viewed each other. By giving governing authority to men, the colonial state introduced a gendered power relationship that probably did not exist before. Intimate as well as civil life was policed by judges, who had been given authority by the Spanish Crown to impose punishment, including the use of stocks and lashes, in order to enforce their laws.

Wixárika social dynamics assimilated the gross inequalities between men and women that had been defined by the colonial state: women were the possessions of men and they should respond to their husband or to a male relative. During the colonial period it became common for authorities to take a ‘tenancha’, an official housekeeper and cleaner who often became the man’s mistress. Such patterns may have led to the institutionalisation and social acceptability of polygamy. As the process of acculturation accelerated after Independence and in the post-revolutionary period, so too did inequality within intimate partnerships and polygamy became institutionally sanctioned. Having more than one wife is now less frequent, although Wixárika law still permits a man to take a second or subsequent partner. This gender unequal order also resulted in intimate partner violence becoming commonplace, a pattern that can be traced back along the lines of colonial and state interventions.

“As they saw us coming several of them were so put out at the unusual sight of the expedition, that they threw down their hats and fled into the forest”

Carl Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1902

(Lumholtz p96)

Carl Lumholtz’s ‘Unknown Mexico’ is one of the most detailed early ethnographic accounts of Wixárika life that pays particular attention to intimate partnerships.

Some years later, in the post-revolutionary 1930s, Robert Zingg again took up the topics of marriage and intimacy between Wixárika men and women:

‘Nowadays adultery creates no more scandal than fornication, and the latter very little. Of adultery casual talk reached me often that such and such lovers, married to someone else, were meeting at the water hole of the arroyo. So little is adultery sanctioned that one of the severest vows taken by a Huichol for favour of the gods is to abstain from adultery for five years… ritually sexual offences are not treated harshly since any contamination of any sexual offence is removed by brushing the offender with grass.’

Robert Zingg

Zingg also wrote of equality between the sexes, coinciding with accounts from central and southern Mexico that women were venerated for their fertility.

‘Among the Huichols women suffer under no ritual handicaps, nor are they considered as inferior or unclean due to the sexual function. On the contrary, female sexuality ties up with Huichols conceptions of fertility and increase so as to give women a high ritual place… Most Huichol gods are women and the greatest of them all, Nakawé, grandmother Growth, is definitely conceived of as an old woman with grey hair. This gives all women, especially old women, a high ritual status as well as a social one’

Robert Zingg

The Coloniality Of Gender And Violence

Alfredo López Austin the eminent historian of Mesoamerica described how reciprocity in the family and the domestic-productive unit, visible in archaeological finds and mythology, strengthens the binary notion of the cosmos and the idea that human value is given as part of a couple.

"For example, they told me 'put yourself in the hands of the ancestors. If you haven’t committed adultery and you have confessed, you are well to have children, the birth will go without problem, and well I always left my life in the hands of ancestors without knowing if I was going to do well. ... That's why I abandoned him [my husband], he always messes with other women, then he brought another woman home, then another. Not anymore! Because of his infidelity, several of my children died” (Rosa, 2021).

These conceptions are the foundation of the coloniality of gender: before colonisation relations between women and men throughout the regions know as Mesoamerica were probably parallel and grounded in reciprocal rights and obligations.

Writing at the turn of the 20th Century, Carl Lumholtz was witness to the changes that were happening in in Wixárika intimate lives:

“The ties of marriage were probably never very strong among the Huichols; yet while guarded by religious beliefs they were far more secure than now, when nothing but the fear of corporal punishment, lashes, and the stocks in prison restrains the people from indulging their fancy too freely”.

(Lumholtz p96)

“The ties of marriage were probably never very strong among the Huichols; yet while guarded by religious beliefs they were far more secure than now, when nothing but the fear of corporal punishment, lashes, and the stocks in prison restrains the people from indulging their fancy too freely”.

The vara de mando (staff of office) was a crucial symbol of power that connected human beings to the realm of their ancestors.

The community of Tuapurie guards their original staffs for the annual ‘cambio de vara’ ceremony. Smaller more modern versions are used on a day-to-day basis and the staff continues to represent the endowment of authority to chosen individuals. In the past these scared items were only for men, as their power made them a potential source of illness for any woman who touched them.

Until very recently government posts were all held by men and this male empowerment defined the patriarchal structure of Wixárika communities, where the authority of the male heads of the family was law. Few crimes were committed but harsh punishments could be used against those who transgressed.

'There remains practically nothing for the judge to do, but celebrate marriage and punish elopements, and to these duties they dedicate themselves with an astonishing zest and vim'

'Unknown Mexico', Carl Lumholtz, 1902

As far back as 1681 the Spanish Crown decreed that Indigenous judges had the authority to physically punish their subjects for minor crimes including civil and religious offences.

“Huichol memory is still clear of the days of the padres when adultery was punished by stripping the offender in public and giving them 25 lashes together with five days in the stocks without food or water” (Zingg 140)

The law permitted ‘six to eight lashes as appropriate’ (Recopilacion de Leyes de los Reynos de las Indias, 1681). Zingg wrote about the use of the whipping post when he visited the Wixárika town of Tuxpan in the 1930s.

Tuapurie Oral History Project: Gender in living memory

Between 2013 and 2022 the Tuapurie Oral History project interviewed women and men from the community of Tuapurie to ask them how gender and women’s lives have changed over time. These conversations have helped us understand how gender relations have become fairer to women in recent decades and how they differed one and two generations ago.

Importantly they are a record of how Wixárika women experienced historical events including violent incursions, the arrival of clinics, school and roads and the role women played in making Wixárika history. Some of this history is told in the animated film ‘Ukari Wa’utsika’, The Stories of Women

You see, women cannot talk, they cannot express an opinion

Rosa, 2013

"When we had the post in Pochotita I saw many women beaten, bleeding, I was beaten. They pulled them by the hair as if they were a sack..." (Sukulima, 2022)

The man was in charge, you had to obey what men said, men could marry as many women as they wanted, they could abuse us, before men beat their wives, even in public, all the time women had purple faces from the beatings

Chabela, 2022

Many women talked about how relationships between men and women are far more equal now than they were in the past.

“Well, we are the ones that are changing things, because before they would say that women were worth nothing”

Wenima, 2022

Now they say that both men and women have the same value and I ask ‘how did we resist so much’? Now you can't beat any woman because they will sue him

Chabela, 2022